Sidrah Ahmad Chan shares a personal reflection on the Call to Prayer Controversy.

Aima Warraich of https://www.instagram.com/niqabaechronicles/

Sidrah Ahmad Chan shares a personal reflection on the Call to Prayer Controversy.

Aima Warraich of https://www.instagram.com/niqabaechronicles/

May

How the Call to Prayer 'Controversy' Can Build Compassion for Muslims with Spiritual Abuse Trauma

Written by Sidrah Ahmad ChanContent Warning: This essay contains discussions and specific examples of spiritual abuse, sexual abuse, and domestic violence

On the first day of Ramadan this year, when I heard the call to prayer (the adhan) emanating through my window as the sun set in my downtown Toronto neighbourhood, I felt frightened.

No, I am not someone who has only heard the adhan played in Hollywood movies about terrorists or in racist television shows like Homeland. And no, I am not an Islamophobe who has bought into white supremacist conspiracy theories about a Muslim “takeover” of Canada. Indeed, I grew up hearing the adhan five times a day in my home. The adhan is as deeply embedded into my happy childhood memories as the distant sound of the ice cream truck approaching from two blocks away.

When I was a kid, when I heard either the call of the adhan or the ice cream truck, my heart leapt, and I would drop everything and run.

As an adult, I have been deeply concerned about the rise in hate crimes against Muslims in Canada, and have conducted research on this issue, interviewing 21 Muslim women survivors of Islamophobic violence in the Greater Toronto Area. I am also a founding member of a grassroots organization that is dedicated to challenging Islamophobia using education and the arts.

So why, at the beginning of Ramadan, when I heard the adhan come up through my apartment window, did my heart clench instead of leap? Why did my stomach turn with fear?

On one level, I was afraid that the adhan would be used as a rallying cry for hate groups.

Indeed, since the call to prayer has played publicly in the streets, we have seen conspiracy theories spread about a supposed Muslim takeover of Canada and selective pearl-clutching about public noise disturbances. To many Muslims in Canada, these stigmatizing reactions feel no different than society’s obsessive fixation on the hijab and niqab -- if it’s Muslim, it’s a problem. It’s sinister. It’s an existential threat.

Although I’m not proud to admit it, part of me wanted to blame the Muslim community for the frenzy over the public broadcasting of the adhan on loudspeakers. If we just turned down the volume, I thought, everyone would calm down. But it is victim-blaming to believe or argue that Muslims are ‘provoking’ Islamophobia through overt expressions of faith. In the same way that women are not responsible for ‘causing’ assault because of the way they choose to dress, Muslims are not to blame for hate levelled against them because of the way they dress, pray, or otherwise express themselves. Whether it be an assault against a woman or an anti-Muslim hate-crime (or both), the responsibility for the violence falls entirely on the shoulders of the person who is committing it.

At the same time, it’s important to recognize that with the threat of Islamophobia looming, anything that signifies ‘Muslimness’ can feel like a lightning rod for prejudice, and people will cope with that stressful reality in different ways. A few of the survivors of Islamophobic violence that I spoke with in my research study stopped reading Quran in public, removed their hijab or niqab, or took other steps to prevent themselves from being identified as Muslim after they were attacked. Other women that I interviewed told me that they felt renewed commitment to outwardly expressing their Muslim identity after they faced a hate crime. I personally believe that both reactions are valid. The painful decisions that are made in the aftermath of Islamophobic violence are deeply personal, and not to be judged or belittled.

After reflecting upon these issues, I reminded myself to not victim-blame the Muslim community for the hateful reactions to the adhan. I thought that this realization would be enough to shift my reaction to hearing the call to prayer from my window -- but I was mistaken.

On the second day of Ramadan, as I listened to the adhan float up from the streets below, I still felt afraid. And very sad.

So I dug deeper to investigate why. And as the faint cry of the muezzin’s (person who makes the call to prayer) voice echoed in my ears, I remembered.

Although I am not comfortable disclosing where, when and how, I will share that at one point in my life, I was harmed by someone who portrayed himself as a teacher of Islam and as a pious, “practising” Muslim. This person could easily quote Quran and Hadith and was respected by others. The abuse was heartbreaking and shattering. And somehow, for some reason, hearing the adhan in the context of a public broadcast was bringing up memories of him.

It has taken me a long time to understand that I have been through spiritual abuse and to grasp the depth of what that means. It’s one thing to acknowledge that you were assaulted or harmed in the physical realm. But what does it mean when violence is perpetrated against your spirit and destabilizes your sense of connection to God or faith? To answer this question, I will explore the issue of spiritual abuse in the Muslim community. Although spiritual abuse occurs in a wide range of religions and spiritual traditions and is by no means unique to the Muslim community, I will provide examples from the Muslim context because that is the intended audience for this essay. I will also share a list of resources on spiritual abuse at the end of this article, most of which have a Muslim focus.

So what is spiritual abuse and what does it look like in the Muslim context? Spiritual abuse can be perpetrated by a romantic partner/spouse, family member, friend, sheikh or sheikha, Imam, a leader in the mosque, a Quran teacher, a spiritual guide, mentor, chaplain, coach, or any other person in your life. It can look like using Islam to justify abuse -- whether it be domestic violence, sexual assault, financial abuse, or emotional abuse. The abuser may claim that Allah ‘permits’ them to behave in this way, or even rewards them for it.

Spiritual abuse can also look like intertwining abuse with religious content. For example, the abuser may say that Allah hates or is displeased with their target while physically abusing them. The abuser may say emotionally degrading things to their target whilst teaching them how to read Quran. Or the abuser may perpetrate sexual harassment or assault, blame it all on shaitan, and then accuse their target of being a bad Muslim they don’t “forgive” the abuser or “cover their sins”. Unfortunately, there is a long list of possible examples of spiritual abuse. At its core level, it is about using religious or spiritual reasoning or content to justify, enable, facilitate, or excuse abuse.

Although spiritual abuse can also be perpetrated by family members, friends, and acquaintances, it is most commonly discussed in the context of religious leaders, teachers, or guides. When people in these positions abuse their power to enact harm against their students or followers, the sense of betrayal -- and the resulting betrayal trauma -- is profound. It is difficult to grapple with an experience where in one moment, someone is teaching you about Allah, and then in the next moment, that same person is abusing you.

In this way, spiritual abuse is intensely painful and confusing. It can create a deep, traumatic association between God and abuse. It can even make it feel like God is the abuser. In this way, spiritual abuse colonizes your religious or spiritual life, filling it with a sense of fear, futility, and despair.

In order to understand the impact of spiritual abuse, it’s important to reflect upon the psychological impact of trauma. Earlier this year, I created a presentation on Trauma and Spiritual Abuse in Muslim Communities for the Hurma Project (Watch on YouTube Below), which is a new initiative that aims to address spiritual abuse in Muslim communities. In that presentation, I explained how if someone faces abuse that was committed in the name of religion or by a religious figure of any kind, they might form traumatic associations with religious practices.

Because researchers have characterized how trauma is processed in the brain, we have learned that in situations of extreme danger, a part of our brain called the amygdala facilitates a “recording” of the dangerous situation. In this recording of traumatic memory, all of the sights, sounds and smells that are present during the dangerous situation are grouped together. For example, if someone is abused by a person who is wearing musk or who has a specific tone of voice, then the smell of musk or that particular tone of voice may be recorded and labelled by the brain as “dangerous” and even “life-threatening” in a traumatic memory.

This is a survival mechanism that helps humans make it through situations of danger and avoid harm in the future. However, a difficulty arises for abuse survivors when, after the violence is over, they go into fight-or-flight mode, have flashbacks, and or feel perilously unsafe if they see, hear, smell, or otherwise experience things that are associated with their traumatic memories. Many people are familiar with the scenario of a combat veteran who, after returning home from war, will duck and cover any time they hear a loud sound. These same kinds of associations can develop for spiritual abuse survivors.

For example, it might seem blasphemous to consider that if someone was abused by a Quran teacher, they might find it difficult to read or even hear Quran. But this is a reality for some survivors of that kind of abuse. Rather than stigmatizing people who have this reaction to the Quran as being “lost”, or accusing them of “not trying hard enough”, we should instead consider the impact of trauma and provide compassion and understanding. Too often, we judge people based on their external acts of worship, and label them as “good” or “bad”. We share platitudes with survivors of spiritual abuse about how they should just pray more. This judgmental mentality leaves no room to breathe or to process how abuse has been intertwined with religion for them, due to no fault of their own. Indeed, when these experiences are shuttered in silence, there is less opportunity to understand the nature of the harm that occurred.

Which brings me back to the adhan.

It is only by writing this essay that I have had an important realization: In the past, in one particularly important setting, I heard the person who harmed me give the call to prayer.

Now that I have reflected more deeply, I have realized that hearing the adhan broadcast at the beginning of Ramadan didn’t just frighten me because of the spectre of Islamophobia. The adhan in this context also, tragically, reminded me of the person who harmed me. In essence, hearing the call to prayer through my window made me feel like the abuser was “coming to get me”. Even though I was listening to a completely different muezzin, and even though many years have passed since the harm took place, I felt like he was coming to get me.

I know this might sound strange, but spiritual trauma can show up in these kinds of elusive ways. Although I understand and have studied the science of trauma, I sometimes still feel ashamed that I have these kinds of reactions. I still blame myself. I wish that hearing the adhan had simply filled me with childhood nostalgia, just like the sound of an ice cream truck still does, rather than a sinking sense of despair.

At the same time, I believe that having been through spiritual abuse has equipped me to be able to spot it when it is occuring on different scales. Indeed, spiritual abuse can be perpetrated at the community level, especially when it comes to exclusion or shunning that is perpetrated by the community as a whole. There are a large number of Muslims who have been “unmosqued” due to poisonous experiences in the masjid. These experiences include anti-Black racism, lack of appropriate responses to situations of domestic violence, being stigmatized or labelled as “haram” because they struggle with addiction, being shunned because of their gender identity or sexual orientation, and/or facing a mosque environment that is not accessible with regards to their physical or mental disabilities.

For these Muslims, hearing the call to prayer from a mosque in their neighbourhood where they ordinarily don’t feel welcome or seen might be bittersweet or even heartbreaking. After self-isolation is over, we must think of the people who will continue to be isolated.

While I bring up these complexities, please know that I am not arguing that silencing the call to prayer from public spaces will solve these problems within the community. But as the frenzy around the adhan has descended into threats of lawsuits, I can’t help but feel that the community is too eager to pour resources into external problems, rather than address issues that are lurking under the carpet.

Indeed, a central aspect of my journey of recovery from spiritual abuse has been centred around breaking the silence and raising awareness about spiritual and other forms of abuse within the Muslim community. While doing this work, I have noticed that the community is more comfortable with hearing about and responding to harm that comes from “outside” sources than abuse that occurs in our midst. Although there are many amazing Muslim activists and advocates who are doing great work to address the reality of abuse, there is still a stigma and silence around the topic. I’ve noticed that if I’m talking about my research on Islamophobia, doors open. When I bring up abuse within the community, doors close.

Very much like trying to switch off the adhan in order to appease Islamophobes, too often, the community “switches off” discussions of abuse in order to try and keep Islamophobia at bay. After all, Muslims know too well how stories of abuse are co-opted and used to demonize the entire community. So, the logic goes, it’s better to just pretend it isn’t there.

But the truth is, it is possible to challenge both Islamophobia from external society and abuse within the community at the same time. We don’t have to choose one at the expense of the other. We can move beyond binary thinking.

Indeed, in the ‘controversy’ about the adhan being played on public loudspeakers, it feels as though there has been room for only two voices: Islamophobes who are whipping up hysteria about the call to prayer, and Muslims and allies who are defending it. Once again, survivors of spiritual abuse, people who have been “unmosqued”, and others with complicated and conflicted feelings have fallen by the wayside in the conversation. In this way, being reactive to Islamophobia encourages black-and-white thinking and reduces our conversations to soundbites. Indeed, it feels as though each of the two “sides” is on a loudspeaker, while abuse survivors are again left whispering in the hallways, hoping someone will pay attention to their needs.

I encourage us to step away from the loudspeakers and listen. There are complicated questions for us to reflect upon, far beyond debates about what volume setting the adhan should be played at. For example: What is the aftermath for Muslims who have been through spiritual abuse? What does it mean when the person who abused you is admired by the community? Where are the supports for everyone involved? Where are the community leaders willing to learn more about this issue and take a stand? What if you are afraid that if you share your story, it will be taken up by Islamophobes who will use it to demonize the entire community? Or what if you are more afraid that your community might accuse you of enabling hate if you speak out?

These are the kinds of questions that Muslims who have been through spiritual abuse ask themselves every day.

I will end this essay by sharing the most recent installment of the story of my complicated reactions to the adhan. The other day, I had a discussion with a friend of mine about the impact that hearing the adhan broadcast was having on me. Although she isn’t Muslim, she had a good understanding of the conflicting layers involved. She showed me compassion and encouraged me to keep reflecting on what the call to prayer means to me. After our talk, my friend sent me an excerpt of one of Rumi’s poems:

For years, copying other people, I tried to know myself.

From within, I couldn't decide what to do.

Unable to see, I heard my name being called.

Then I walked outside.

When I heard the call to prayer that evening, I walked to the window to listen more closely. I closed my eyes and accepted the complex realities of Islamophobia, spiritual abuse, and spiritual hunger all occurring at once.

I thought deeply about what I am called to do as someone who has been through spiritual abuse. Although there were no simple answers given to me at that moment, I realized that sharing honestly, calling for compassion, and holding space for more nuanced conversations were important steps to take.

After the adhan was over, I looked out at the indigo-blue sky while the sun sank below the horizon. I felt a glimmer of Love.

And I decided to write this for you.

Sidrah Ahmad-Chan is a PhD student at the University of Toronto where she is studying the intersection of Islamophobia and gender-based violence. She is also a founding member of the Rivers of Hope Collective.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

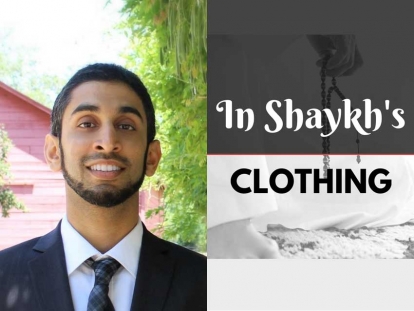

The beautiful artwork accompanying this essay was created by Aima Warriach, who you can follow at @niqabaechronicles on Instagram.

I would like to give thanks to my friend Nada Conic, who sent me the Rumi poem, and who encouraged me to think more deeply about my reactions to the adhan.

I also want to thank my friend Dewi Minden for challenging me to think about victim-blaming and the adhan.

Finally, thank you to thank Hana Shafi, Nakita Valerio, and others who engaged in discussions with me as I worked through my feelings surrounding the adhan.

RESOURCES ON SPIRITUAL ABUSE & ABUSE IN GENERAL

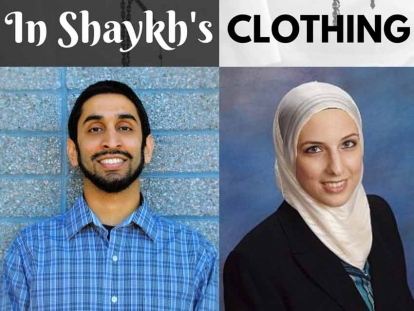

In Shaykh’s Clothing, a resource website for spiritual abuse in the Muslim community.

The Hurma Project, a project dedicated to upholding the sacred inviolability of all who enter Muslim spaces from exploitation & abuse by those holding religious power & authority.

HEART Women and Girls, an organization dedicated to ensuring that all Muslims have the resources, language, and choice to nurture sexual health and confront sexual violence.

Facing Abuse in Community Environments (FACE), a Muslim-focused organization dedicated to fostering safe community environments by holding abusive religious and community leadership accountable.

The Assaulted Women’s Helpline (available to residents of Ontario). This helpline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and provides support in English and up to 154 other languages. 1-866-863-0511. TTY: 1-866-863-7868.

No Excuse For Abuse provides resources and information on how to support people who are living with abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic.

FURTHER READING ON TRAUMA

Steve Haines. (2015). Trauma is Really Strange. (Graphic Novel)

This article was produced exclusively for Muslim Link and should not be copied without prior permission from the site. For permission, please write to info@muslimlink.ca.