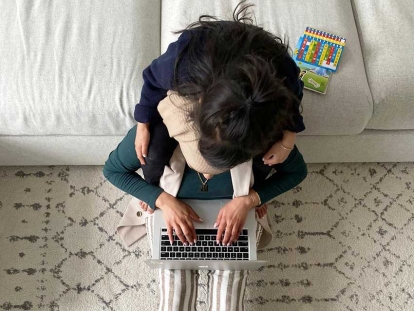

The photo "Isolation" is from Hanan Hazime's "Pandemic" Photo Series. Visit https://hananhazime.com/ to learn more about her work.

Hanan Hazime

The photo "Isolation" is from Hanan Hazime's "Pandemic" Photo Series. Visit https://hananhazime.com/ to learn more about her work.

Hanan Hazime

Nov

Challenges Faced by South Asian Canadian Muslims Living with Mental Illness and their Loved Ones

Written by Zehra Kamani(*Names have been changed to protect the privacy of the individual/family)

“The greatest griefs are silent,” wrote Wally Lamb, author of “I Know This Much is True”.

Recently adapted into an HBO miniseries produced by and starring Mark Ruffalo, the story portrays a heart-wrenchingly tragic and illuminating story of identical twin brothers, Dominick and Thomas Birdsey, the latter of whom lives with paranoid schizophrenia. While it serves the very necessary purpose of raising awareness on mental illness, perhaps one of the most appealing dimensions of the story, and less discussed in the world of mental health, is the portrayal of the many silent griefs experienced by the loved ones of those living with a mental illness - the complex melange of love, anger, stress, loss of personal identity, and an unyielding sense of duty to family. Ruffalo conveys, through an Emmy-award winning performance, the anguish that Dominick faces as Thomas’s brother and caregiver amidst a complicated backdrop of tragedies and difficulties in his own life.

Samiya* is all too familiar with this complex reality. Her mother, Fatima*, has lived with chronic depression for the majority of Samiya’s life.

“[My mom] has two stages - depression, and a stage where she’s “okay”. Over the years, I noticed that in the stage when she’s okay, she wasn’t really okay,” describes Samiya.

Fatima has lived with her illness for two decades. Samiya started noticing it at a very young age, but it became progressively worse as she grew up, and was a significant problem by the time she turned 8.

“Suddenly she didn’t feel like talking to people anymore. She would start staying in her room. She would start sleeping a bit more, a few more hours, until it became the whole day where she would sleep.”

“I remember her telling me that her brain freezes. Even taking a shower, [she asks] ‘How do I take a shower? What am I supposed to do?’ She hates that feeling.”

Fatima’s depression follows a cyclical pattern. She eventually transitions out of the “down” phase -- of being withdrawn, lethargic, and unable to conduct daily life activities -- into a more energetic phase, similar to the manic phase seen in bipolar disorder. Over the years, her “down” phase has become progressively longer. Her latest down phase has lasted for three years - the longest it has ever been.

When Fatima is in her “energetic” phase, this can be even more challenging for Samiya and her family.

“She wants to do everything. She’ll start ten things, but won’t finish them. She wants to talk to everyone. She wants to go out. It’s a complete other side. It’s hard to calm her down… because she can get offended very easily. It’s a very fine line that we walk during this stage. As a family, there’s more friction.”

Samiya was pushed to grow up at a very early age because of her mother’s illness. By the age of 11, she was cooking meals for her family. At 16, she could run the household and was helping raise and take care of her younger brothers, including changing diapers and feeding.

“I feel alone,” Samiya says. “As a child, I feel like I didn’t have support. I didn’t feel like I had a mom. Especially as a child, you think your mom is your best friend. I didn’t have that. I had to take care of my family… even though I had school. My dad would apologize to me on my mom’s behalf. He would tell me to try and be patient. I had to be the mom and the support factor for everyone else. That’s why I feel more alone. If I break, then everyone will break.”

According to a Statistics Canada study in 2012, 38% of Canadians aged 15 or older reported having at least one family member with a mental health issue. Amongst these Canadians, one-third (35%) felt that their time, energy, emotions, finances or daily activities have been affected as a result of their family member’s illness. They reported lower rates of life satisfaction and general health.

Dr. Farah Islam, a researcher, mental health advocate, and educator, has studied the South Asian population in Canada extensively. She found that South Asian immigrants show higher rates of anxiety disorders and self-reported stressful life events than Canadian-born South Asians. Being a female immigrant also increased the risk of having a negative mental health outcome.

Another 2016 study on ethnicity and mental illness in Ontario also shows that the South Asian community has a higher rate of schizophrenia than the general population, and that South Asians show higher rates of being admitted involuntarily to the hospital for psychiatric reasons.

“This really speaks to the incredible barriers South Asian populations, and other racialized groups face when trying to seek mental health services,” explains Dr. Islam. “Involuntary hospital admission is one of the worst conduits of getting into the mental health system as it is associated with poorer outcomes and is truthfully traumatic in most cases.”

Dr. Islam asserts the importance for community members speaking out and sharing their experiences as one of the most powerful evidence-based ways to fight the stigma that people with mental health issues face.

She also suggests that places of worship have a big role in de-stigmatizing mental illness.

“If our South Asian imams, pundits, gurus, and priests in our places of worship can talk about mental health on the pulpit, tackle misinformation, and encourage community members to seek mental health care – it can help normalize the process and allow people to get the help they need,” Dr. Islam says.

Samiya recalls the stigma she experienced when speaking to family-friends about her mother’s illness and the struggles they faced as a family.

“The second you tell someone, they just start asking questions or giving their input,” Samiya recalls.

She cites awareness and acceptance as two things that the community needs to work on.

“I feel like there’s this misconception of depression -- that you’re just extremely sad about something, that something must have happened in her past that she’s dwelling over,” she explains. “It’s not just that. It’s a chemical imbalance... Sometimes people are so certain about what it is. They don’t know the full story, what every day entails. It’s very frustrating.”

Nadia*, a young adult who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder 1 (manic depressive disorder) as a university student, hopes to help in destigmatizing mental illness.

“A person with a mental illness suffers silently and in addition to that has to face people’s judgments,” she says.

Nadia went into psychosis when she was in university. She painfully remembers the experience of hearing voices, seeing hallucinations and losing control over herself. Fortunately, her family called for help and she was admitted to Mount Sinai Hospital’s mental health program for the first time.

“I have been lucky to have a great support circle, but I know someday I will face [people’s judgments],” she says. “And that might be the very trigger for stress and my symptoms to appear.”

“To be highly sensitive and have to manage the ups and downs of your emotions on a continual basis requires a lot of strength. And then to take the steps to better yourself as a person and continually keep your head high and spread positivity takes even greater strength.”

Nadia’s strength in the face of her journey with bipolar disorder is seen through her multitude of achievements. She was accepted into medical school in 2013 while battling a then-undiagnosed illness, and simultaneously facing the pressures of life as a university student and as a new immigrant to Canada.

Since her diagnosis, she has participated in a play at a local theatre, a feat that she holds great pride in because of the challenge of her symptoms recurring during rehearsals. Nadia has also started a small business in designing and selling T-shirts. She has even written a children’s book, and maintains a blog on the side.

“When the battle is happening invisibly, it compounds the struggle. Celebrating small recoveries becomes impossible at times because they are unseen. We just need to show sensitivity and empathy to people with mental illnesses… so they don’t have to fight discrimination and judgment in addition to their ailments,” Nadia says.

Nadia receives the support of her psychiatrist, social worker and team of nurses. She has also found that her relationship with her family and friends strengthened after she received her diagnosis, all of which have helped her on her journey.

“I’ve been lucky…” Nadia says. “I became more open and transparent with [my parents] and they have been more supportive and understanding toward me. My younger brother has been a solid rock of support without whom I wouldn’t have healed the way I have today.”

However, for some, like Fatima, living with a mental illness can strain relationships.

“I had a rocky relationship with my mom growing up,” Samiya recalls.

“There was always friction between us. It was constant fights, and being a kid, I was getting yelled at. But now I know it wasn’t her. She was still sick.”

Through Fatima’s battles with her depression, Samiya continues to fight on the sidelines with her own battles, finding her place in her family as a daughter, sister, and wife.

“This whole experience is a huge part of my personality, of my childhood,” she notes. “It has an impact on who you become as a person.”

Now, at 28, Samiya’s commitment to being there for her mother through her illness and for her brothers as they cope remains unwavering.

“We’ve managed to stick together as a family. I’ve gone through some of my own life experiences, so just going through that has opened up my eyes more,” Samiya says. “The way we are able to view it now, it’s different from when we were younger. So that’s something I’m proud of.”

This article was produced exclusively for Muslim Link and should not be copied without prior permission from the site. For permission, please write to info@muslimlink.ca.