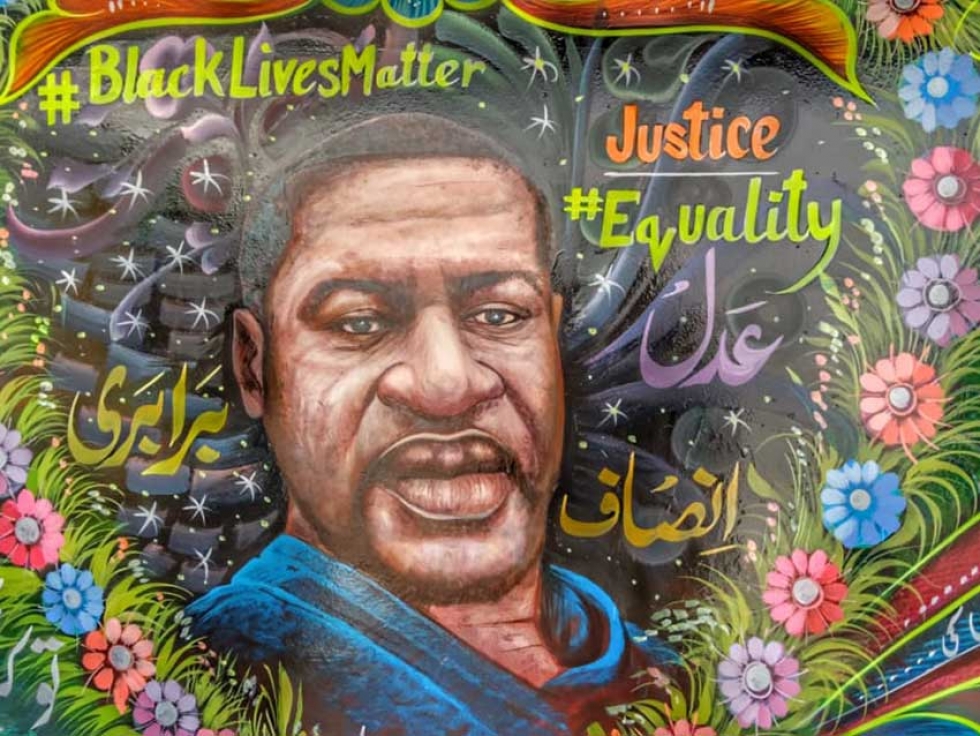

Pakistani truck artist painted a mural depicting George Floyd surrounded by a colorful heart-shaped garland of flowers, with slogans such as #Black Lives Matter on one side and #justice and #equality on the other.

Haider Ali

Pakistani truck artist painted a mural depicting George Floyd surrounded by a colorful heart-shaped garland of flowers, with slogans such as #Black Lives Matter on one side and #justice and #equality on the other.

Haider Ali

Oct

2020 and the Islamic New Year: How Tragedies Can Invoke Beauty

Written by Zehra Kamani2020 has had an apocalyptic feel from its very onset.

Amongst the incidents that afflicted the world this year, 2020 saw the outbreak of the coronavirus and the hundreds of thousands of deaths that ensued worldwide, coupled with the decline of global economies, with a loss of 3 million jobs in Canada since April; the ill-fated Ukraine International Airlines flight 725 that was shot down in Iran, killing all on board; the deadly explosion in centre of Beirut, Lebanon that is said to be one of the most powerful non-nuclear explosions in history; massive bushfires in Australia that have killed an estimated one billion animals; some of the worst wildfires California has seen in history; continued conflict in Yemen, supported by arms sales by Canada, is tearing apart the nation and leaving millions, including babies and children, on the brink of starvation; the detention of an estimated one million Uighur Muslims in internment camps in China amidst deplorable conditions, abuse, and gross human rights violations; and civil unrest in the United States following the shootings of George Floyd and Jacob Blake amidst a backdrop of police violence against Black people.

From one dismal event to the next, humanity was reminded time and again that we have been doing something, or many things, very wrong, tiptoeing into 2020 on an already very worn out tightrope.

Starting off a year in tragedy is nothing new for those who commemorate each new year of the Islamic calendar in the month of Muharram with the tragedy of Karbala. Muslims, predominantly those of Shiite background, as well as people of other faiths including Hussaini Brahmin Hindus and Christian Iraqis, express their grief at the heinous killing of Imam Husayn, the grandson of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), along with his family members, young and old, and companions. These individuals stood up against the tyrant ruler of their time, Yazid ibn Muawiya. Yazid was the face of brutality and injustice of his era, and besides the tragedy of Karbala, is most known for his indiscriminate killing of thousands of civilians in the event of Harrah, as well as for sanctioning the rape of women and his utter disregard for the well-being of his people, placing precedence instead on his personal luxuries and entertainment.

While the commemoration of the tragedy of Karbala is an important religious event on the Islamic calendar that is marked in both communal and personal ways, it is meant to be a reminder that history inevitably repeats itself, and from which to derive lessons on human nature, behaviour and ethics.

If ever there were a time to take a lesson from the event of Karbala, it would be now.

In the present COVID-era, with families home-bound and with the upheaval of economies and social structures that we have become so accustomed to, “normalcy” has been upended. For some, including myself, 2020 has become the year of re-evaluation -- of thoughts, day-to-day behaviours and priorities that once made so much sense.

Perhaps one of the biggest lessons from the tragedy of Karbala comes from Zaynab (p), the sister of Imam Husayn (p) who was present in Karbala to witness the atrocities committed against her family, including the murder of her two young sons, and the abuse and imprisonment of the women and children of her family. Zaynab (p) became the face of the social movement that ensued, who, through word of mouth, spread the word of Yazid’s crimes in what became the earliest form of majalis (or gatherings of commemoration) of Imam Husayn (p). The power of her words created a movement among the masses that ultimately led to Yazid’s downfall. Zaynab’s famous words, which were valiantly spoken to a crowd of Yazid’s supporters while held in captivity resonate today : “I see nothing but beauty.”

Amidst all the tragedies of 2020, beauty may seem remote.

Even so, the beauty that Zaynab (p) found in an ugly reality rife with injustice was the beauty in seeing the silver lining. She foresaw a major “awakening” of the masses as a result of what her family experienced. And this is exactly what happened -- with time, the narrative turned against Yazid, and public sympathy returned to the family of Prophet Muhammad (p).

Although injustices continue across the globe, faint silver linings are emerging worldwide.

On May 25, after the callous killing of George Floyd, the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement was reignited and sent shockwaves throughout the globe. From high profile athletes, such as players of the NBA who boycotted the playoff games following the August 23 police shooting of Jacob Blake, to the general public, more and more people are mobilizing and acting by realizing the influence of their individual actions. They are bringing the movement home rather than simply applauding the actions of others whilst sitting on the sidelines.

In the weeks following Floyd’s death, many protests in support of the BLM movement began gaining momentum in the Greater Toronto Area. However, with all of the media frenzy surrounding Floyd and Blake in neighbouring U.S., it was not hard to miss what was happening in my own backyard. When 29-year old Regis Korchinski-Paquet, an Indigenous Black woman, fell to her death from her 24th floor Toronto balcony in police presence, thousands took to the streets of Toronto to protest yet another fatality at the hands of the police. However, earlier this year, the families of Black Canadians Jamal Francique and D'Andre Campbell who were shot by police in Peel Region had organized demonstrations demanding answers, although media only really started looking at these stories after interest in BLM due to incidents in the US, raised interest among Canadians. These families are now offering their support to the family of Pakistani Canadian Ejaz Choudhry, who was also killed while unarmed by police who were called to do a wellness check on him. Although Black people make up less than 10% of Toronto’s population, they represent 61% of cases in which police used lethal force.

As a byproduct of the BLM momentum, many also took to social media to question the subtle biases and discrimination to which they, too, contribute. People began having more conversations about the history of oppression against Black people, not only in North America, but in their respective cultures and homelands. For example, people of South Asian descent, like myself, called themselves out for preserving a culture of inherent racism. From seeking fair skin at a young age as a symbol of status and beauty to preferring light-skinned spouses, racism and colorism is a deeply ingrained problem in South Asian mentality.

In Pakistan, where my roots lie, and home to the largest population of Black people in South Asia, the Black community is derogatorily referred to as “Sheedi”. They were brought to Pakistan as slaves between the first and the 20th centuries, not unlike the history of the U.S., which, having been born in Canada, is the story I am more familiar with. It was only in 2018 that a Black Pakistani politician (also notably female, Tanzeela Qambrani) was elected into parliament. Many Black Pakistanis marry outside of their community in an attempt to appear less Black, a result of the discrimination they have endured for decades. The unfair and unfortunate consequence is the loss of their African culture.

The reignition of the BLM movement worldwide instigated consumers to call out the companies they support for further perpetuating discrimination, such as Johnson & Johnson and Unilever, whose skin lightening creams appeal to the “darker” skinned female seeking to meet warped beauty standards in South Asian countries. With increased public pressure inspired by the BLM movement, these companies have decided to rebrand and drop the use of “fair”, “whitening”, and “lightening” from their products. While these products continue to exist, being mindful of the language we use is an important step towards longer lasting change.

Another silver lining that appeared in a similar fashion occurred in the fashion industry. Big fashion brands like H&M, Gap, Adidas, Zara, and Nike have profited off of the ethnic cleansing of China’s minority Uighur Muslims by sourcing cotton from factories in Xinjiang, China, the homeland of Uighurs. These companies also employ thousands of detained Uighur Muslims as forced “slave” labour, who receive little to no income. China is the main supplier of the world’s cotton, and over 80% of the cotton from China comes from Xinjiang, so complicit silence by these big brands who pump out fashion labels globally represents a significant international human rights problem. When these companies were called out, including on various social media platforms, H&M made a statement indicating that it would end its relationship with a Chinese yarn factory, Huafu, which reportedly used forced labour in its factories. H&M also stated that it will no longer source cotton from Xianjing.

These are ways in which change has been inspired, albeit through tragedy, at the grass-roots level.

The majalis of Imam Husayn (p), whereby religious scholars and speakers commemorate and derive lessons from the tragedy of Karbala, has also become an important platform for education and change for many Muslims around the world. This month of Muharram, it seems that some speakers made a concerted effort in bringing forth these necessary discussions in their lectures.

For example, in her lecture series, Tahera Kassamali, a religious scholar and advisor for women at the Jaffari Community Centre, also explored how we submit to dominant narratives, whereby society dictates, overtly and subtly, and often without our conscious awareness, what is seen as right or wrong, good or bad, desirable or undesirable. Kassamali led her audience to question the narratives that surround how we view Black people, Indigenous people, and, in a secular society that looks down upon religion, religious people. She discusses one root of this problem is from serious biases and flaws in the education system, where entire communities’ truths and realities and rich identities have been distorted or completely shut out from textbooks. These include Islam’s rich contributions in its Golden Age from the 8th to 14th centuries while the West was submerged in the Dark Ages; the crimes and atrocities committed against the native and Indigenous peoples at the hands of colonizers; and a discussion of Black history in a context beyond slavery and violence. Kassamali noted that this erasure of a people’s history erodes one’s sense of identity, leaving us even further susceptible to passively accept the dominant narrative of our society.

Further, in his lectures this Muharram, Syed Asad Jafri discussed the emphasis on collectivism in Islam, that Islam is a socially responsible religion in which the merits of communal prayer far outweigh individual prayer, a religion in which we are recommended to celebrate communally at births and marriages and new beginnings, but also come together and speak up when our neighbours are ailing and grieving.

Discussions like these, while overdue, are upshots of a growing collective consciousness. This is the beauty of social movements. It starts as one small spark with one individual, and becomes a catalyst for something much larger. This is what happened in Karbala, and arguably what is happening today. In the current COVID climate, where the value of individual growth and personal achievements have plummeted, people are beginning to recognize the importance of their place as part of a social fabric, a larger humanity. The way I see it, 2020 has become the year of the collective. Perhaps the inspiration of these movements is precisely why millions mark each new year by commemorating a historical tragedy.

As one poet eloquently states, “...while our new year is not marked by celebration, it is marked by inspiration and rejuvenation. It symbolizes the rise of justice in the face of injustice, love in the face of hatred, and freedom in the face of slavery” (@thebarefootedbeliever).

So although 2020 has hit us hard, it may just be the cold bucket of water that we needed to wake us up from our passive, silent, submissive, autopilot state, to start becoming aware and vocal and ultimately “become the change.” Only then can we truly “see nothing but beauty” as Zaynab did.

This article was produced exclusively for Muslim Link and should not be copied without prior permission from the site. For permission, please write to info@muslimlink.ca.