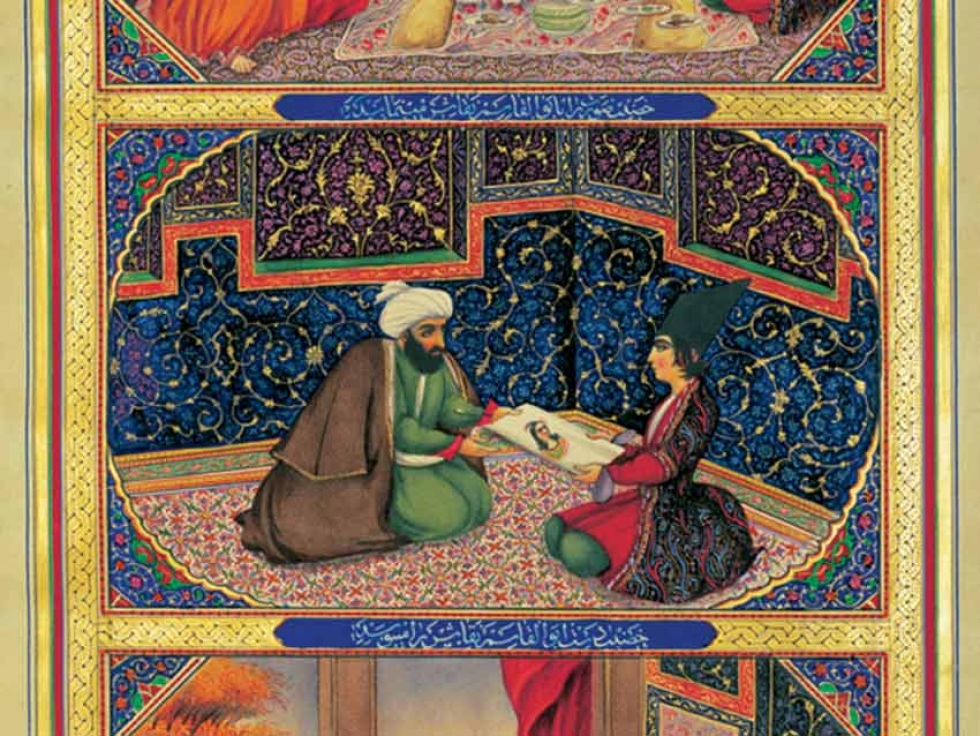

Scheherazade and the sultan by the Iranian painter Sani ol molk (1849-1856) in One Thousand and One Nights.

Wikipedia

Scheherazade and the sultan by the Iranian painter Sani ol molk (1849-1856) in One Thousand and One Nights.

Wikipedia

Sep

How the Arabian Nights stories morphed into stereotypes

Written by Katherine BullockThe conversation over Justin Trudeau’s blackface had widened to a conversation about anti-Blackness in Canada, and stereotypes of Muslims and anti-Arab racism.

The issue first surfaced when Time magazine ran a photograph of Trudeau at a private high school event dressed as Aladdin in brown make-up. If he had dressed as Aladdin without make-up on his face and hands would it have been OK?

The answer is no. Aladdin draws on hundreds of years of anti-Muslim sentiment in western culture.

Myths circulated for hundreds of years

Aladdin became known in Europe and North America as part of a story in The Thousand and One Nights — also known as The Arabian Nights, a manuscript based on Middle Eastern and South Asian folk tales. The Arabian Nights was once one of the most popular books in Europe and North America and held that place for at least 350 years.

It was, and remains, a rich source of material for western artists to draw upon in their creative works. Stock stereotypes are recycled in new, but recognizable ways; the latest rendition being the new release of the movie Aladdin, staring Toronto’s Mena Massoud as Aladdin.

Aladdin was not part of the original manuscript but appears to have been inserted into the collection by the French translator, Antoine Galland, whose edition, published between 1704 and 1717, became a phenomenal success according to the late Iraqi-American islamologist and arabist, Muhsin Mahdi. Even though the original Arabic readers would have been able to distinguish the fantastical elements of the stories, they were treated by translators, publishers and western scholars as ethnographic material.

This slip from story to ethnography has been very damaging to Muslims in both western discourse and policy. The stories have been interpreted to highlight the real exotic otherness of Arabs/Muslims and all of the stereotypes that go with that including: their barbarity, their seclusion of women, their being bound to tradition, the lack of rule of law and so on.

All of which is the bedrock to contemporary discourse about Muslim men as violent and women as oppressed that lead to discriminatory policies as Edward Said wrote in his 1978 seminal book, Orientalism.

Real-life implications of ‘Orientalism’

When in 2015, a polling agency decided to poll people on the potential U.S. bombing of Agrabah, the Disney-created fictional city in which the fictional Aladdin and Princess Jasmin lived, 30 per cent of Republicans and 19 per cent of Democrats supported the bombing.

The tradition of blackface, as discussed in The Conversation by Philip Howard, has an unnamed parallel history in western society: dressing up and pretending to be an “Oriental.”

“Oriental” is now used to talk about what used to be called the “Far East” — a Eurocentric term for China and Japan. At its inception, it meant the lands of Arabia — the “Near” and “Middle East.”

From 1790–1935, before American political interests and geopolitics introduced the stereotypes of the religious radical or terrorist, Americans turned as consumers to the “Orient” as a place to raid in constructing their identities.

Theatrical performances, cigarettes and chocolates were promoted with “Oriental” names and images, along with high art traditions and academic work, travel narratives, and spin-off stories using Oriental plot, narrative, mood and images.

People decorated their houses with Oriental curtains, cushions, painting and objets d’art. They dressed up as “Orientals” for parties. The society now known as the Shriners was established in 1870 as Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine. This group even incorporated corrupted “Oriental” traditions, sayings and dress into their men’s clubs. One of the club rituals was a kind of “hajj,” where they would enter the room after whispering the password “Mecca” to get in. In the centre of the room was a black pedestal decorated with a scimitar next to a table with a black cloth upon which was placed a Bible, a Qur'an and a black stone. They would face the “Orient,” saying a “Grand Hailing Salaam” and bow with arms raised forward.

In 1923, there was a Shriners’ parade down the “Road to Mecca” and a “Garden of Allah” reception at the White House with President Warren Harding and the First Lady.

Trudeau opened the conversation

Trudeau’s brownfaced Aladdin thus encapsulates a problematic history, western privilege (Blackface and Oriental dress-up), ripping off what became negative stereotypes of other cultures for their own pleasure and amusement.

My research with investigative journalist Steven Zhou of Muslim reactions to Disney’s Aladdin found many viewers impressed by the artistic value of the production, but offended by its images and message. Many of them commented how Aladdin and Princess Jasmin costumes, or “Arab” masks for Halloween are not innocent fun to them.

Having an Arab play Aladdin and tinkering with the most problematic aspects of the original cartoon does not fix the problem either. Replacing the infamous cutting the hand scene by a merchant trying to take Jasmin’s bracelet is simply a slightly different wine in the same bottle.

Anti-Muslim racism intersects with anti-Black racism. Considering that Muslims are living under the negative gaze of the security establishment and much of wider Canadian society, this needs also to be addressed, as part of a wider approach to removing racism.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]![]()

Katherine Bullock, Lecturer in Islamic Politics, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.