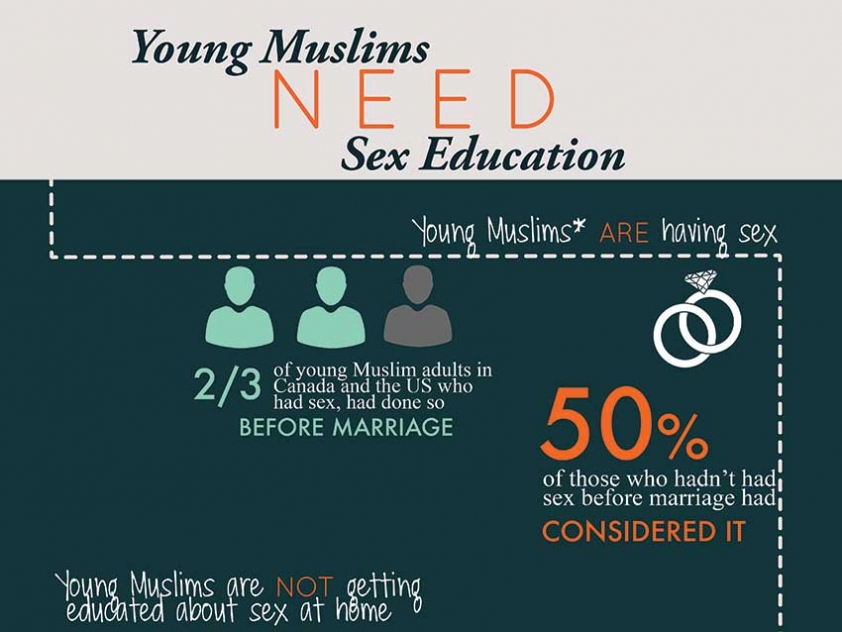

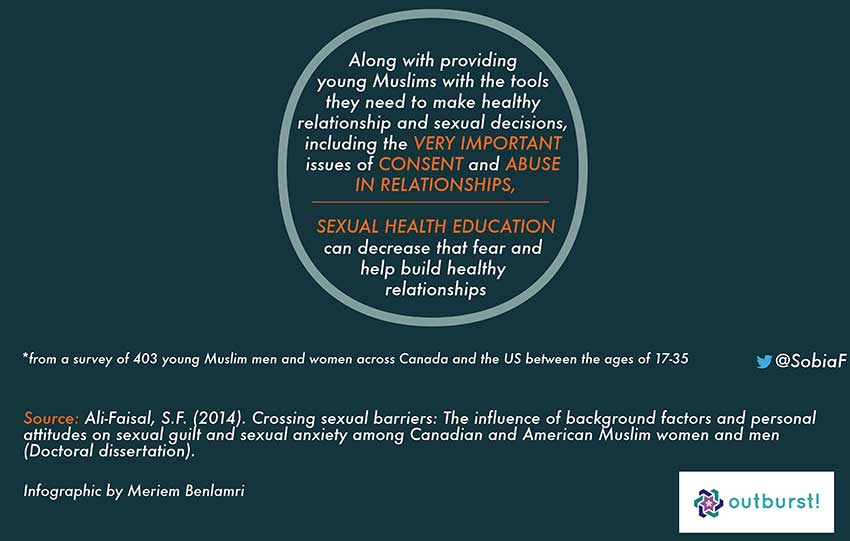

An infographic developed by Meriem Benlamri based on Sobia Faisal-Ali's research.

Courtesy of Outburst

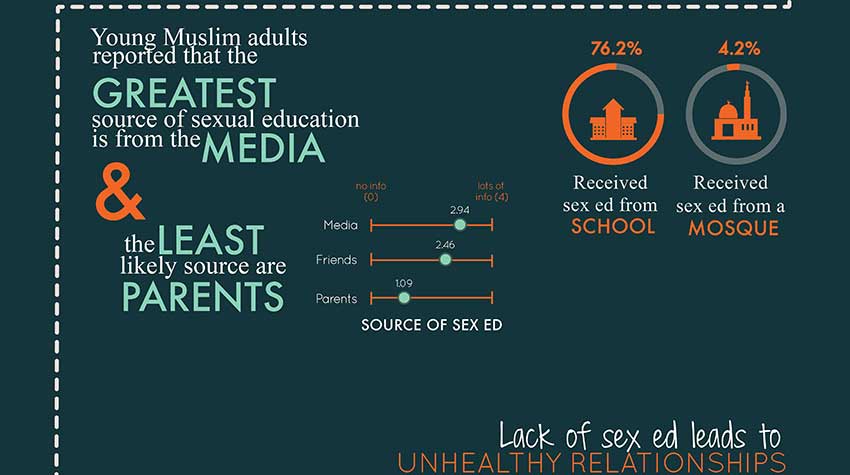

An infographic developed by Meriem Benlamri based on Sobia Faisal-Ali's research.

Courtesy of Outburst

Jun

North American Muslims & Sex Ed: Looking at Sexual Guilt with Researcher Sobia Faisal-Ali

Written by Chelby DaigleIn response to the conversations emerging from opinion pieces we have published on the new Ontario Sex Ed curriculum, Muslim Link is starting a series of interviews with several members of North America’s Muslim communities on sexual education. We’ll be exploring the challenges Muslim Canadians, especially Muslim youth, are facing in relation to sexual health education and morality.

Sobia Faisal-Ali, a PhD researcher who conducted a survey of 403 North American Muslims between the ages of 17 to 35 exploring issues of sexual health education and experiences, shares her findings with us.

Tell us about yourself.

I'm of South Asian descent and was raised in the Maritimes. I completed my BA (in Psychology) at the University of Prince Edward Island, and my MA and PhD at University of Windsor in Applied Social Psychology.

For my Master's work, I focused on acculturation and ethnic identity of South Asian Muslims, but for my doctoral work I switched the focus to sexual health issues, particularly sexual guilt and sexual anxiety.

Why did you choose to research the topic of sexuality and North American Muslims?

To be honest, the topic came to me in some ways. During my time as a PhD candidate, I switched supervisors. I wasn't as interested in what I had been studying before and things needed to change. The research area of the supervisor I switched to, Dr. Charlene Senn is sexual violence against women, but she had some background in sexual health. So I decided to focus on that. As I was doing my literature review it became clear that there was virtually no research on the topic of sexual health and Muslims and that this research really needed to be done.

How did you go about conducting your research?

It was a long process, but my project involved a pilot study in which I had focus groups of young Muslims, mostly women, evaluate my measures for sexual guilt and sexual anxiety. I wanted to make sure they were appropriate for use with Muslims. They gave some great feedback which I incorporated into my work.

The main study involved online surveys which were distributed across Canada and the US. Participants could fill out the surveys in complete anonymity, which was important to me. I posted the link to my surveys on Facebook, Twitter, in list serves, and I asked some blog writers if they would advertise it for me. I also emailed friends and family and asked them to pass it along. Basically, a lot of snowballing. I collected data for approximately 3-4 months after which time I started my data analyses.

Could you give us an idea of how many of those who contributed were based in Canada?

Approximately one-third of participants were based in Canada.

What were some of your key findings?

What were some of your key findings?

The focus of my research was on sexual guilt and anxiety and how certain variables (sexual attitudes, gender role attitudes, sexual experience, parents' sexual attitudes, and conservative religiosity) worked together to contribute to sexual guilt and anxiety. Some of the key findings were that conservative religiosity, in other words, holding more conservative religious beliefs, and sexual attitudes strongly contribute to sexual guilt and anxiety. The more religious people were and the more conservative their sexual attitudes, the higher levels of guilt and anxiety.

Could you unpack “conservative religiosity” for our readers? “Conservative” is a very relative term which can mean different things to different people.

It's based on a survey I used, which includes over 20 questions. I totaled the scores on the survey, the sum of which reflected the overall level of conservative religiosity. An example of a conservative religious belief would be holding the belief that men and women should not shake hands or that [the] genders should be segregated.

Did any of these findings surprise you? If so, which ones?

I think the finding that surprised me was that so many Muslims, both men and women, reported having had sex before marriage. To be honest, I shouldn't be surprised, but I think I was surprised, pleasantly, that people were comfortable admitting it.

The impact of sexual guilt is explored in your research. Why do you feel that this was important to look at when exploring the issue of sexuality and North American Muslims?

The impact of sexual guilt is explored in your research. Why do you feel that this was important to look at when exploring the issue of sexuality and North American Muslims?

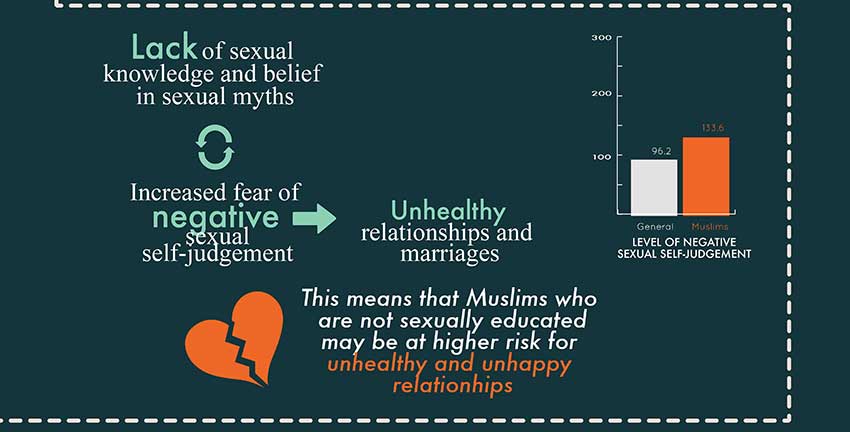

Sexual guilt, as defined in the literature, refers to a fear one has of judging themselves for either engaging in, or potentially engaging in, sexual behaviours. It's a bit more constant, similar to other forms of guilt. And like regular guilt, it does not need a particular sexual event to be triggered. One can feel sexually guilty because of one's beliefs, one's experiences (e.g. being taught that sex is a sin), etc.

I thought it was important because sexual guilt has actually been related to problems within relationships, including within marriages. And yes, sexual guilt can last into marriage as well. From conversations with Muslim friends it seemed like something relevant to Muslims.

Islam as a religion does not condone premarital sex but generally takes a relatively very positive attitude towards sex within marriage? Did you find that those interviewed associated sexual guilt with premarital sex only or sex even in marriage? If so, and I'm not sure this was in the scope of your research, why?

I actually didn't interview anyone about sexual guilt so I'm not sure if that relationship exists. It's an interesting one to explore. My sexual guilt measure did not specify sex within or outside marriage, either, for most questions. So I'm not sure if there was a relationship. What I can say is that those who had sex before marriage actually had lower levels of sexual guilt than those who waited until marriage. Now, this was a correlational association so it could be that those who had lower levels of guilt were more likely to engage in sex before marriage, or it could be that sexual guilt levels decreased for those who engaged in sex before marriage. Not sure which direction the relationship is in. It could also go both ways.

You recommend that sex education is needed for Muslim youth. This seems to be coming up in the context of the current Ontario sex education debate. But based on your own research, it seems that many of those interviewed did get sexual education at school but the perceptions of sex from the home and community seem to also have had an impact.

If you agree with this statement, are you not really arguing for additional religious sexual education and ease with discussing sexuality within Muslim homes and communities?

Yes, most did report receiving some sexual education at school. I didn't assess whether perceptions of sex from the community had an impact, though I did find that parental sexual attitudes were not related to levels of sexual guilt.

What I did find was that the participants in my study reported that parents were the least likely source of sexual health education. My arguments for sexual education of Muslim youth has more to do with my findings around sexual guilt and how it relates to the previous research. I think my answer to your next questions explains what I mean.

Based on your research, how is the lack of sexual health information and guilt around sexuality affecting Muslim marriages?

Based on your research, how is the lack of sexual health information and guilt around sexuality affecting Muslim marriages?

I found that the participants in my study had higher than average levels of sexual guilt, compared to averages found in previous research with non-Muslims. The issue is that the research has found sexual guilt to be related to dysfunction in sexual relationships which in turn can result in problems such as depression in women and breakdown of relationships. One thing that has been found to be related to less sexual guilt is having fact-based sexual education. So I believe that sexual education can be an important tool in creating healthy sexual relationships.

Outburst, a Toronto-based project which works with young Muslim women on violence prevention, has turned some of your key findings into an infographic which we have included throughout this article. How would you like to see other parts of Ontario's Muslim community use your research?

I would like the Muslim community to look at the statistics and see that sex is a reality for young Muslims. Regardless of whether or not parents want their children to wait until marriage to have sex, it appears that many will not wait. I think the Muslim community has to understand that reality and figure out what they want to do with that information. I can't tell them what to do. That will depend on what they think is best, but I do know that punishment or attempts to control behaviour probably won't work. The research actually shows that when young people are educated about sex they tend to delay having sex. That's because they are better prepared to negotiate sexual situations.

Honestly, I think that if parents want their children to wait until marriage to have sex, the better option will probably be a combination of fact-based sexual education from a young age—because who knows when children will have to face sexual decisions—combined with religious teachings about sexual relationships.

Sobia Faisal-Ali can be found on Twitter here.

This article was produced exclusively for Muslim Link and should not be copied without prior permission from the site. For permission, please write to info@muslimlink.ca.