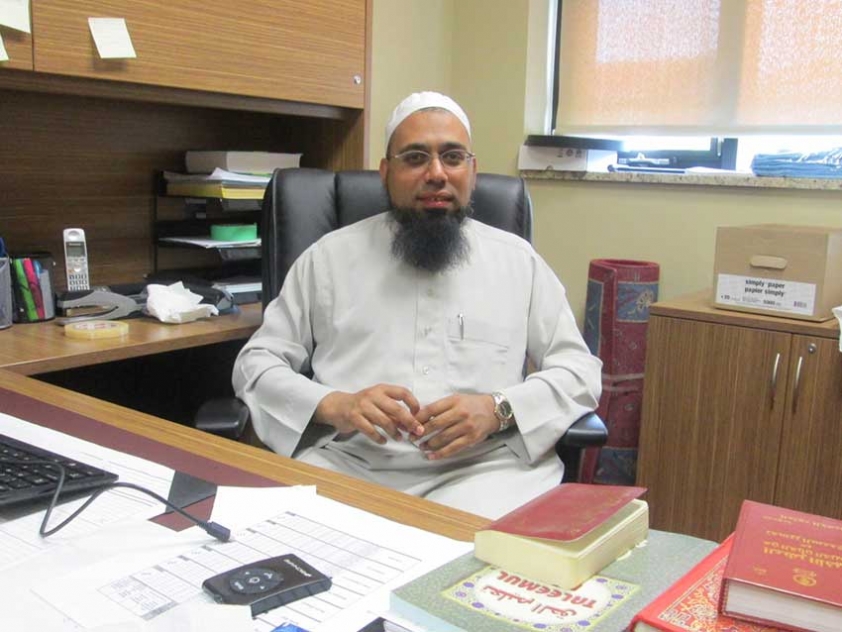

Imam Mohammed Badat of the Islamic Society of Cumberland (Masjid Bilal)

Muslim Link

Imam Mohammed Badat of the Islamic Society of Cumberland (Masjid Bilal)

Muslim Link

Aug

Imam Mohammed Badat was born and raised in Toronto, Canada to parents who emigrated from Gujarat, India in the early 1970s. His family grew up near their local masjid in York region. “The masjid was our playground growing up,” he shared. Imam Badat began his Islamic Studies there, memorizing Quran and being tutored by the resident imam.

Imam Badat’s father was the first to suggest that he consider pursuing his studies in order to become an imam. “My father noticed that there was a disconnection between the community and the masjid because a lot of the imams were coming from abroad, they weren’t very fluent in the English language. The kids weren’t understanding the imam and the imam wasn’t understanding the kids so the purpose that was to be achieved by the imam in the masjid wasn’t being achieved in its totality. So my father suggested that I should consider being an imam as someone born and raised here in Canada,” Imam Badat explained.

At the age of 17, Imam Badat and his younger brother Yusuf, who is now also an imam in Toronto, were sent to finalize their study of Quran at an institute in Gujarat not far from his family’s village. After 2 and half years of study, the brothers returned and graduated from high school.

“My father wanted me to study at university or college in Canada but I felt that I had started something so I wanted to continue my Islamic Studies,” Imam Badat explained. Imam Badat chose to pursue his post-secondary Islamic education in South Africa at Darul Uloom Zakariyya. Imam Badat arrived in 1994, the year apartheid ended in the country. The university is located in Lenasia, which under apartheid was an exclusively Indian township south of Soweto, not far from Johannesburg. Today, the area is far more racially diverse and the dramatic changes in the area and the country became the backdrop for Imam Badat’s Islamic education. “Being in South Africa has taught me a lot, particularly about respecting people, no matter what culture, race, or faith they belong to, at the end of the day they are the creation of Allah,” he explained.

Tolerance was one of the main focuses of Islamic education at Darul Uloom Zakariyya, an institution which caters to an international student body who are mainly planning to go to the West to become imams. “Because in the West, you will encounter people from all over the world, including Muslims from all over the world,” Imam Badat explained, “There are diverse communities, people who come with different cultures, so they really emphasized to us that you can’t have an attitude that ‘it’s my way or the highway’. They tried to highlight those prophetic teachings and practices of the companions where they went to different parts of the world and they were able to embrace the culture and society but they were also able to promote the pristine message of Islam without offending people.”

Imam Badat felt that South Africa was an ideal place to study to be an imam as it is a country where Muslims are also a minority. “Muslims in South Africa practice their religion in full but you also see the local non-Muslim community have embraced them well,” Imam Badat explained, “Everyone is living in harmony; everyone respects each other for what they are. That is something positive I have seen and experienced and have learned to instil in my personal life. You have to accept that everyone is not going to be like you.”

Graduating with a Bachelor’s and Masters’ Degrees in 2000, Imam Badat returned to Canada. Not too long after his return, he was approached by the administration of Masjid Bilal in Orleans. Imam Badat remembers the days of leading jummah prayers in the small house that once stood where the present mosque now stands. Imam Badat expressed that it has been quite rewarding to see the initiative to build a mosque in Orleans come to fruition during his tenure as imam.

One of the unexpected results of the masjid finally being built was the increased ethno-cultural diversity of those coming to jummah prayers. “When I came to the masjid in the beginning it was a predominantly South Asian community,” Imam Badat explained, “but when the masjid was built-Wow! Many of these people were already living here but because they didn’t know that this small house was the masjid they would be traveling to other parts of the city for religious services. But now when they see this beautiful structure, everyone is now, mashallah, connected and the masjid has become a magnet for the community.” The diversity of the Orleans Muslim community is now reflected in everything from the makeup of Masjid Bilal’s board to the students who attend the Masjid’s weekly educational programs.

Imam Badat feels that in order to support the development of an ethno-culturally diverse masjid community tolerance and engagement are key. “Everyone has contributed towards the Majid. If someone has come with a good suggestion, embrace it. The easiest way to make someone feel a part of the masjid is to go and meet them, say ‘Assalamu Alaikum brother or sister, how can I help you?’ You have to break that barrier with the first greeting, when they see that you are smiling, you are a person who is approachable, they will feel welcome,” Imam Badat shared.

Imam Badat also feels that it is important for the imam and mosque board members to be accessible to the wider community. “After jummah prayer, most of our board members are always in the back greeting people,” Imam Badat explained, “After I finish my prayers, I go to the back and just greet people ‘Assalaamu Alaikum Brother, where have you been, I haven’t seen you in a while.’ Every Friday, the sisters come down and they want to see the imam; they come to my office. That’s what helps to give a sense of belonging to people so they feel that this masjid is for everyone. That way people feel like this masjid is their masjid.”

But along with ensuring people feel welcome and at ease in their local mosque, Imam Badat feels it is important that the mosque’s non-Muslim neighbours also feel at ease. “One of the greatest challenges we face today is Islamophobia, everyday there is something new,” he shared, “but only Muslims can change this image.” Masjid Bilal regularly hosts school visits, particular for students from the local Catholic schools. Their neighbours have also been encouraged to visit the mosque. Imam Badat also shared a story about befriending a local construction crew who were building near the mosque. “They had a lot of questions about Islam, so I bought them some Yaseen Pizza and chatted with them,” Imam Badat explained, “Casual encounters like this can really help to change perceptions.”

In the wake of the Prophet Mohammad (pbuh) cartoon controversy, Imam Badat ran a series of lectures about the miraculous feats of the Prophet (pbuh). He felt that the best way to challenge hate-mongering was to celebrate the Prophet (pbuh)’s life and achievements. These lectures have been compiled into the book “Astounding Manifestations from the Pride of the Universe Mohammad (pbuh)”which is available at Masjid Bilal and you could read an except online here.

Imam Badat and his fellow Ottawa-Gatineau imams have also been active in giving back to the Ottawa community, by once again helping to fundraise for the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO), an initiative spearheaded by Imam Anver Malam of Masjid Jami Omar. This has even included manning the phones at the yearly CHEO telethon. Masjid Bilal partnered with the Ontario Electronic Stewardship by becoming a drop-off point for the recycling of electronics. The proceeds from this were donated to CHEO. “As Muslims we are part of this community so we have to give back to it,” Imam Badat explained.

But on top of leading jummah prayers, teaching at the masjid school, giving lectures, and bridge-building in the wider community, Imam Badat has to do some serious support work for Muslim community members.

Imam Badat is the Muslim chaplain for Monfort Hospital. Each day he receives a list of Muslim patients to visit. “I go there to give them moral support. People often get depressed in hospital, particularly if they have no family in the city or who can visit them. I also see many patients who are in hospital for addiction and mental health issues. They just need someone to talk to and to listen to them.” Imam Badat explained. This isn’t the sort of work his Islamic university education prepared him for. “This is not something you learn in school,” he explained, “You have to take it upon yourself to learn.” So whether it be talking to a student dealing with suicidal thoughts, counselling a divorcing couple, visiting someone at the local detention centre, or assisting the police with translation, Imam Badat has had to learn about what it is to be an imam in Orleans on the job. Imam Badat takes these challenges in his stride but does his best to avoid being too late for dinner, “My wife isn’t happy if I’m late for dinner,” he shared rather sheepishly.

One piece of advice Imam Badat would give to aspiring imams based on his own experience is to stay humble. “Don’t say to yourself ‘I’m the imam!’ Your knowledge should not give you arrogance. You are not ‘the imam’. You are more like an older brother to the community. You have to keep this idea in your mind in order to maintain a sense of humility.”

This article was produced exclusively for Muslim Link and should not be copied without prior permission from the site. For permission, please write to info@muslimlink.ca.