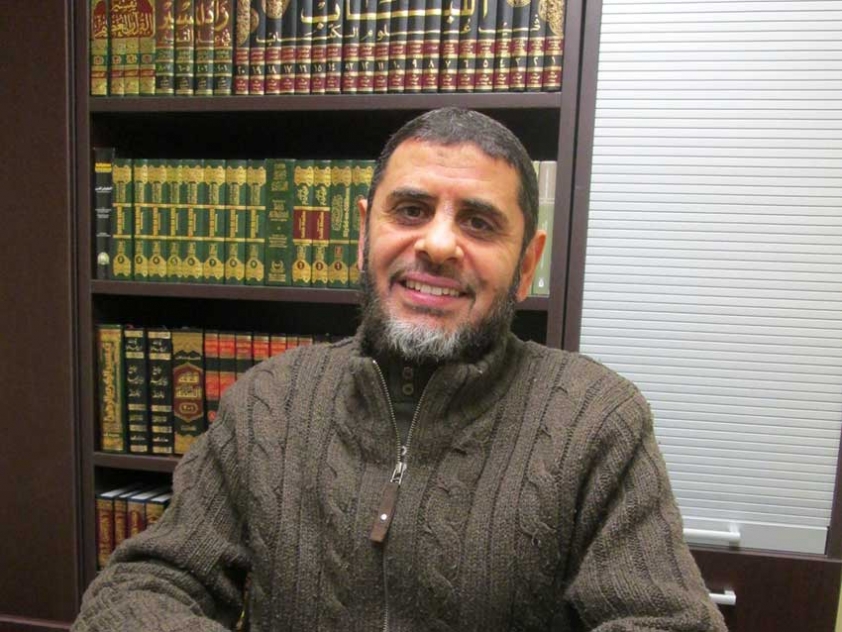

Sheikh Ismail Albatnuni at Masjid Assunnah in Ottawa South.

Chelby Daigle

Sheikh Ismail Albatnuni at Masjid Assunnah in Ottawa South.

Chelby Daigle

Jan

Sheikh Ismail Albatnuni was born in 1964 in Tripoli, Libya. From an early age, he sought out Islamic knowledge, memorizing the Quran, and eventually studying Maliki fiqh (a school of Islamic jurisprudence) from local scholars. However, he knew if he ever wanted to take his studies further it would mean having to leave his homeland.

"In Libya at that time, it was very difficult. Qaddafi shut down all of the Islamic universities," Sheikh Albatnuni explained. Instead, Albatnuni made the practical choice to study engineering and computer systems. However, in 1992, he left Libya to study at a branch of Al-Imam Muhammad Ibn Saud Islamic University in Ras Al Khaimah (UAE) because he was "very eager to study sharia." After graduating, he went on to teach Islamic Studies at Khalifa bin Zayed Air College.

Life was good for Sheikh Albatnuni and his young family living in UAE. He had a good salary and was able to enjoy the "luxurious" lifestyle on offer in the Emirates. He was far away from the political repression in Libya, where some of his friends and colleagues who had been imprisoned for their opposition to Qaddafi had been killed in the 1996 Abu Salim Prison Massacre. But his comfortable life was not to last. Sheikh Albatnuni was warned that he would need to leave the Emirates for his own safety as Qaddafi was rounding up people he had deemed political opponents. And so, Sheikh Albatnuni found himself applying to Canada as a political refugee.

In 1999, Sheikh Albatnuni, his wife, and three young children arrived in Vancouver, Canada. Going from a well-off life in the Emirates to a refugee in Canada was a traumatic transition. "But what made it even worse was I didn't speak any English. I couldn't even really say my own name properly," Sheikh Albatnuni stated.

Concerned about the social isolation he and his wife were experiencing in the city, which had few Libyans at the time, he decided to visit some friends in Ottawa to see if it might be a better place for his family. "I liked Ottawa so much. But I was lucky I came in July," Albatnuni said with a laugh, "maybe if I had come in winter, I would not have liked it so much!"

Despite eventually realizing just how bad Ottawa winters are, Sheikh Albatnuni, doesn't regret bringing his family to Ottawa where it was easier to find a support network of fellow Libyans and Arabic-speakers. He eventually studied English for two years at Algonquin College and went on to work as a teacher of Islamic Studies at Ottawa Islamic School. He is now the imam of Masjid Assunnah, located in Ottawa-South, an area with the highest concentration of Muslim residents in the city. "With the help of Allah subhannawatallah (Glory and Exalted be He), we have made a good life here," he stated.

Sheikh Albatnuni feels that his own experience coping with the difficulties of being a refugee in Canada puts him in a good position to support the many families he sees coming to Masjid Assunnah who are also struggling with the pressures of immigration. "We understand the pain they go through," he said. He has seen this be particularly difficult on marriages, sometimes leading to divorce. He tries to provide what support he can, and encourages people to speak with him if they are having problems.

One of the problems Sheikh Albatnuni admits he faced when coming to Canada was getting used to Western culture. "Canada changed me a lot," he said, "When I came here, I had to rethink a lot of things. I had to try to understand this society." Sheikh Albatnuni is grateful to his teachers and the education he received from Ibn Saud Islamic University for giving him the foundation to be able to judge what is Islamically required and what you can be flexible on. He feels his own journey has helped him support other immigrants and even young people who feel conflicted between their religion and Canadian culture. He receives a lot of questions related to issues like the wearing of niqab (the face veil), insurance, and interest (riba'a). He feels strongly that more Muslims with means need to start creating initiatives, such as scholarships, if they want to see less students taking loans with interest. "You have to provide people with alternatives," he stated.

Sheikh Albatnuni runs two halaqas (prayer meetings): one at the University of Ottawa on Fridays after Isha prayer (night prayer) and one at Masjid Assunnah on Sundays after Isha prayers. Both halaqas are in English "because I don't want anyone to feel left out". Sheikh Albatnuni feels it is important that people take the time to learn Islam from a real person. "Don't take your deen (religion) from the internet. Take it from a person who is in front of you, who you can talk to," he stated.

Although he thinks there are great resources for learning Islam online, he has also become very concerned about websites that are leading young people to take on extremist views. He has had young people ask him about the content of these websites, particularly the websites encouraging young people to join ISIS.

"I explain to them the real meaning of jihad. I tell them that people going and fighting in Syria have just made it worse for the Syrian people." He is very concerned about the issue of radicalization to violence and how some young Canadians have left to join ISIS. Based on his own work with young people, Albatnuni fears that groups like ISIS who glorify dying in jihad are able to attract young people who are finding it difficult to cope with the struggles of daily life. "They offer a quick ticket to Jannah (heaven)," he stated, "but in life there is no easy way out, you have to struggle. You have to struggle with desires, with parents, with school, with finding a job, building a family. You can't think that the surest way to Jannah is to go and be killed in jihad! You should struggle to have a long life full of good deeds. Part of our job here as imams is to help our children to go through the struggles of this life."

"Youth are looking for someone to trust," Sheikh Albatnuni explained. But he feels that a challenge facing many older members of the Muslim community is how to build trust with youth. "The youth, they see what we are doing. If we say we are doing this for them, we are building this masjid for them, we are having this program for them or this conference for them, but we don't work with them, we don't ask them what they need or they don't see any results, we lose their trust." He understands that sometimes it might be frustrating for older members of the community to listen to young people with patience, but he feels that that is what is necessary in order to build trust. "Let young people talk about whatever they think and speak what is in their minds, we need to listen to them," he added.

Sheikh Albatnuni feels that young people can benefit from the wisdom and experience of older members of the community. He particularly feels that he has been able to support young people, who in their desire to become better Muslims, start to feel they have to reject everything about Canadian culture. Because of his own struggle to understand Canadian society, he feels he can help young Muslims appreciate what Canadian society has to offer. "They have taken it as a guarantee and they do not appreciate it," he explained, "This society is a very educated society. I'm not talking about academic education, I'm talking about respect. Here people look to understand the opposite opinion. They have a dialogue. This is what we lack back home. Where we come from it is 'my way or the highway': either you follow me or you are my enemy. Here we have freedom of religion. I can apply Islam here much more than where I came from." However, Sheikh Albatnuni is critical of Canadian anti-terrorism policies which he feels are just fostering distrust between law enforcement and the Muslim community. "The surveillance, the spying, this reminds me of Libya. They should work with us to help the youth. These are their children too. These are Canadian children."

Whether it be improving relations between law enforcement and the Muslim community, or between Muslim youth and older members of the community, Sheikh Albatnuni feels that trust is the key. "Any successful work in the community needs two pillars- the youth and the elders. The youth bring energy the elders bring wisdom. But to work together, we need to trust each other."

This article was produced exclusively for Muslim Link and should not be copied without prior permission from the site. For permission, please write to info@muslimlink.ca.