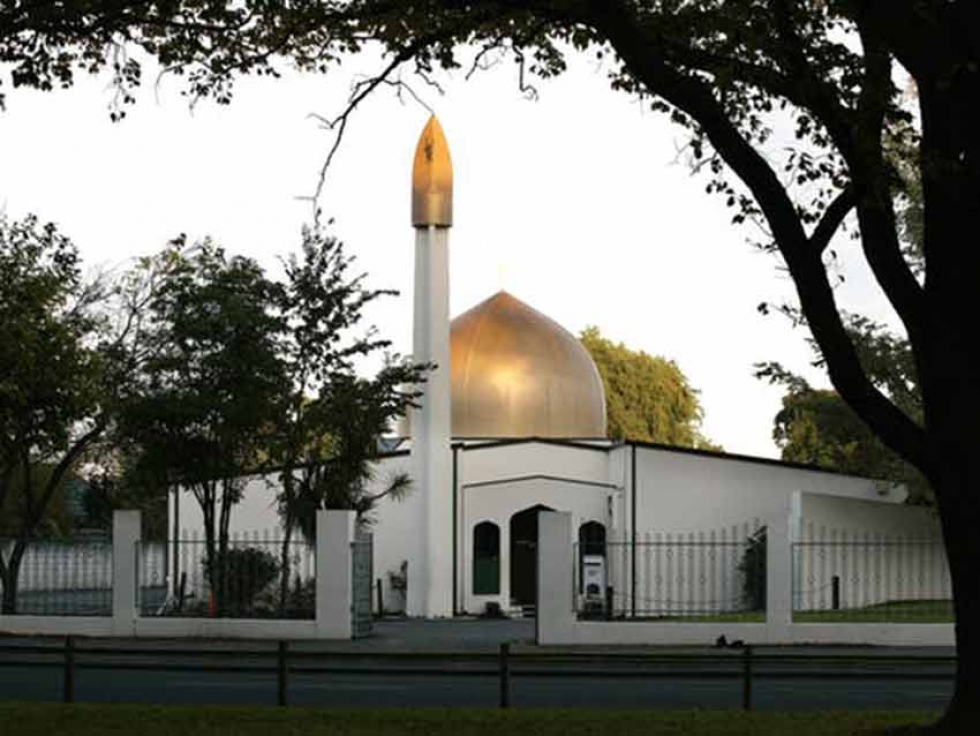

Al Noor Mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand, the site of the Christchurch mosque attack.

The Conversation

Al Noor Mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand, the site of the Christchurch mosque attack.

The Conversation

Aug

When life means life: why the court had to deliver an unprecedented sentence for the Christchurch terrorist

Written by Alexander GillespieWas Brenton Tarrant’s silence and acceptance of sentence in court a final act to expand his notoriety? Was his disavowal of previously expressed ideological views a trick?

A person capable of planning the Christchurch mosque attacks so methodically may well have mapped the last public chapter, too. By saying little and expressing no real remorse, alone and without even his own lawyer, was he hoping the world would see a determined stoicism, an enigma?

Or did he simply realise the controls around court behaviour were so well designed that he couldn’t hijack proceedings?

For now at least, we can’t know. All we can say for sure is what the court has heard over the days leading to today’s sentence of life in prison with no minimum parole: using overwhelming firepower against defenceless civilians he took the lives of 51 men, women and children, injured many more and left even more bereft.

His silence notwithstanding, then, he is not an enigma. As the first person in New Zealand to be convicted of terrorism, he comes from the same dark place that spawned the likes of Anders Breivik in Norway, Darren Osborne (who drove a truck into Muslim worshippers in London in 2017) and Dylann Roof (who attacked black parishioners in a South Carolina church in 2015).

Tarrant had even carved the names of Alexandre Bissonette (who attacked a mosque in Quebec in 2017) and Luca Traini (who attacked African migrants in Italy in 2018) on the magazines of his guns.

So now he joins that list of mass murderers, animated by a hatred of tolerance, equality and multicultural values, who came to believe indiscriminate violence against unarmed civilians was justified.

The first ever non-parole sentence

If this was America, he could have been sentenced to death or given a cumulative jail sentence of over 1,000 years. Neither option is available in New Zealand. There are many good reasons for having no death penalty, including in this case the denial of any aspirations to martyrdom.

The most extreme penalty New Zealand law does allow is jail for life without any minimum parole period. Although a sentence of 30 years without parole has been imposed, life without parole has never been given.

It is fair to say that Judge Mander, who did an excellent job throughout, met public expectation with his decision to ensure Tarrant never again walks outside a guarded wall.

What the law demands

Such a sentence is justified if the court is satisfied no minimum term of imprisonment would be enough to satisfy the main considerations: accountability, denouncement, deterrence or protecting the community.

In short, the Sentencing Act sets out the purposes of sentencing: to hold the offender to account for the harm done to the victims and the wider community, to denounce the crime and deter others from replicating those acts.

Supplementary principles a sentencing judge must consider include the gravity of the offending and its seriousness compared to other types of offences. The judge is required “to impose the maximum penalty prescribed for the offence if the offending is within the most serious of cases for which that penalty is prescribed” (unless there are mitigating circumstances).

The only mitigation that would have carried weight in this case was Tarrant pleading guilty and therefore shortening proceedings. Other mitigating factors, such as remorse or offers to make amends, were not to be seen or were deemed not genuine.

Placing the victims first

The other principle Judge Mander had to take into account relates to the effect of the offending on the victims. As the 91 victim impact statements heard over three days made clear, those victims displayed remarkable fortitude, bravery, wisdom and humanity. But the black hole of pain the killer left in his wake is near incomprehensible.

Further aggravating factors justifying this sentence were that these were pre-meditated crimes of hate, terrorism, particular cruelty and involved the use of weapons.

Tarrant ticked all of the boxes. The enormity of his crimes made them unlike anything that had gone before. New Zealand has experienced mass shootings in the past, and murders based on racial hatred, but nothing of this scale.

On top of that, no one had employed the internet to spread hatred as happened in Christchurch, nor has anyone pleaded guilty to an act of terrorism before.

When all of these considerations were put on the scales of justice, Judge Mander would have seen that, small acts of mitigation aside, an unprecedented sentence was the only appropriate outcome for an unprecedented crime.![]()

Alexander Gillespie, Professor of Law, University of Waikato

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.