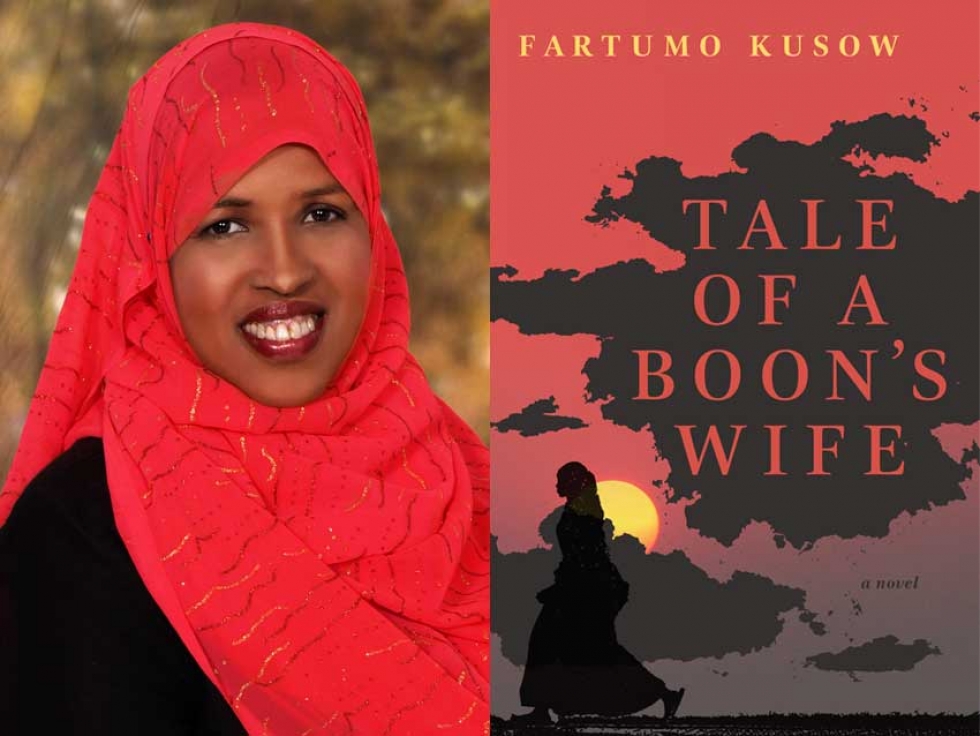

Fartumo Kusow's first English-language novel, "A Tale of a Boon's Wife", is published by Second Story Press.

Fartumo Kusow's first English-language novel, "A Tale of a Boon's Wife", is published by Second Story Press.

Dec

From ESL Student to Canadian Novelist: Interview with Author Fartumo Kusow

Written by Chelby DaigleSomali Canadian author Fartumo Kusow has spent much of 2018 traveling across Canada, the United States, with stops in the UK and Somalia, speaking about her first English-language novel "A Tale of a Boon's Wife", published by Second Story Press.

A high school teacher in Windsor, Ontario, Fartumo has written a novel exploring the impact of social hiearchies in Somalia on the lives of everday people before, during, and after that country's civil war.

Muslim Link interviewed Fartumo about her personal story and how she came to write her first English language novel after coming to Canada as a refugee knowing no English in the 1990s.

The Educated Farmer's Daughter

I always liked languages. Both of my parents were farmers. My father could read at a basic level, but my mother can’t read or write. They were both clear that my sister and I would receive a good education, just as good as my brothers got. I hated it at the time when I was young because girls were allowed to drop out of school and do whatever but my father wouldn’t allow it so I went to school 6 days a week from 7 in the morning to 1 o clock and then I went to a school to memorize the Qur’an from 3 to 6 every evening and I memorized it by the time I was 13, and once I finished memorization I went to Sharia class to study Islam more in-depth. So, I think all of this studying put me at an advantage when it came to eventually learn English.

Writing and Losing Her First Somali Novel

I had my first novel, "Amran" published in the national paper in 1984 in the Somali language.

I decided to write a novel because I was really socially awkward and didn’t understand the games that the girls played and how you interacted with other people. I, also, didn't understand why girls my age was gossiping or getting into fights with each other. I was treated very well at home, with respect, so I could not relate to this behaviour. So I always had a hard time making friends and being liked at school. Coming home after school was like going to heaven each day.

To combat this, my father gave me a book and said, "Everything you hear in the schoolyard, all the gossiping, you don’t talk about it, write it in this book instead! You can bring it to me and I’ll tell you if it’s ok to talk about what you heard with other people."

Eventually, I got tired of writing about the gossip and started changing it into stories.

There were stories of girls who were being forced into marriages for a certain number of cows. In my mind, I thought what would happen if a girl were to run away and not accept this, so I wrote a story of a girl who ran away from a forced marriage.

The national paper picked it up and serialized it in the paper. It was a very controversial subject and people couldn’t believe the story was written by someone so young.

I lost my copy of the stories because of the war. I thought it was lost forever but it ends up that the Library of Congress keeps a record of papers from around the globe.

I contacted the Library of Congress and got a copy.

From ESL Student to English Teacher to Canadian Novelist

I came to Canada and I was going to learn English and write for a wider audience. I always had this feeling like I had something to say, something to contribute to humanity in general. I don’t have the skills for fundraising and things like that, so I think writing is my social activism.

I was always going to be a novelist that, so the goal was going to university and getting an English degree to write beautiful novels. That was the idea.

But when we immigrated to Canada, the struggles of being a refugee got in the way. There was a whole lot of trauma that I didn’t even expect.

When it comes to helping refugees come to Canada, you need to pay careful attention to their experiences of trauma. Because when we first come we don’t really show our trauma because of the survival mode that we're in. It is when the dust settles, and the basic needs are looked after that the ugly image of the trauma refugees suffered comes to the fore.

Because of this trauma, my marriage failed, and I ended up a single mother with five children. I had to adjust, earn a living and keep a roof over our heads. There was no time to even think about writing a novel.

Somali is my first language and I learned Arabic as a second language. I didn't speak any English. I worked at night and attend ESL classes during the day. It took me four years to gain admission to the university.

Even when I finished my Bachelor of Education at the University of Windsor, I never thought I would be hired as an English teacher in the public school board. I coupled my English degree with Biology because I never thought I would be hired as an English teacher. I speak with an accent, English is not my first language, also I’m wearing this scarf on my head. I remember a friend telling me if you’re going for the interview with the public-school board, don't wear your scarf.

"Go without your scarf to get the job and you can wear it later," She encouraged me.

I said “no.” If it’s meant for me to get the job, I’ll get it, but I’m going in with my scarf. In the end, the English degree was what gave me the job. I was hired right out of the teacher’s college as an English teacher.

It was like that with my writing; I never thought my novel would be published but I thought I have to write and at least put the story on the page. I received at least 100 rejections before getting my novel accepted for publication. It took me six years from starting to write to getting published. I started in November of 2011 and it was published in October of 2017. Editing and writing and all that took about 3. Then I started sending it, starting with agents. I would pick 10 or 15 agents and wait and get rejections. For the most part, they don’t give you reasons why you’re rejected. They just say they’re not interested.

Then I started sending to smaller publishers all over Canada. Then Second Story Press wrote me a letter and said “We really like the story but there are things we’d like to see improved. So if you can do this and send it back we will consider it.” I said thank you very much, I appreciate it and I’ll tell you when it’s done.

Writing about Social Injustice in Somalia

I’m using Somalia and these Somali characters as a vehicle to tell a universal human story.

I examine what happens when we ‘other’ people when we decide that some people don’t deserve the same protections, the same human connection, and dignity as we do. I also explore what happens when we decide not to take responsibility for this injustice and the role in which we play in allowing it to continue to happen. In order to rectify it, we have to say, “this is a problem we have created, how can we fix it?” We must take responsibility for our role in this as human.

I focus on Somalia, but Canadian readers should be able to see the parallels with social injustices in this country.

One of the most beautiful characters in the novel is one of the characters who is an "other", and this fact highlights what we lose as a society when we decide a group of people are an “other” and don’t deserve to be included. Canada or Somalia are nations that need their people to survive. But the way our systems work, it's like we are going to war but kicking out half of our soldiers because they don’t belong in our group, but now they also can't help us to win this battle.

I grew up in a home where we could bring up issues and ask questions. We always talked about things that didn’t work. I was critically thinking about the tribal system from a young age and trying to hold myself to account in playing part in this injustice. Also, if you’re witnessing something unjust, you should do something about it. I think we’re all going to be asked when we die about what we did about the unjust events we saw when we were alive. I think this novel is a small attempt on my part to do something about this injustice.

"A Tale of a Boon's Wife" is available in Indigo stores across Canada and can be ordered online.

To learn more about Fartumo Kusow, visit her website here.

This article was produced exclusively for Muslim Link and should not be copied without prior permission from the site. For permission, please write to info@muslimlink.ca.