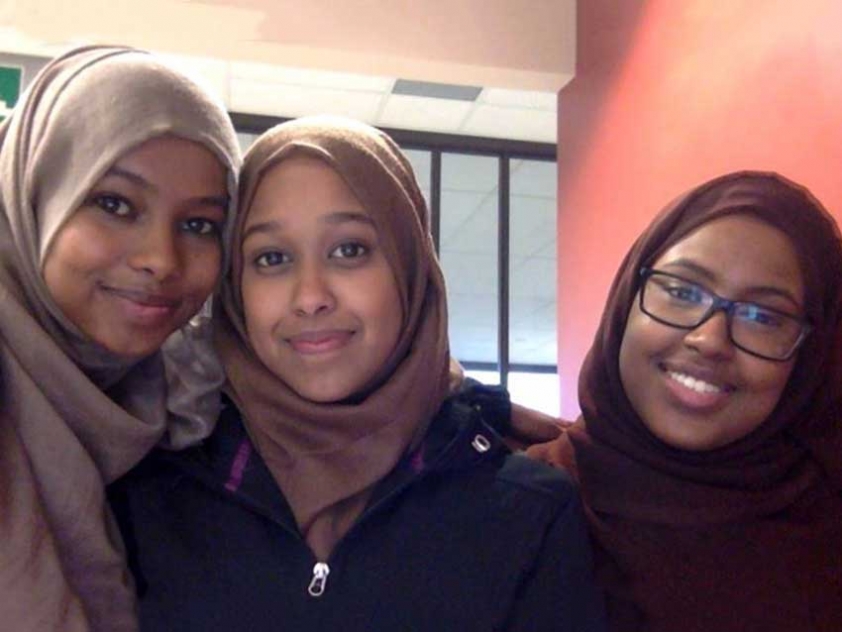

Ramla Said, Sumayya Mohamed, and Halima Abdisamed made a video confronting the reality of racism in Ottawa's Muslim Communities.

Ramla Said, Sumayya Mohamed, and Halima Abdisamed made a video confronting the reality of racism in Ottawa's Muslim Communities.

Mar

Ottawa Students’ Film Highlights Experiences of Racism in the Ummah

Written by Muslim Link“Racism in the Ummah”, a short film by a group of students from the University of Ottawa, received an Honourable Mention at the University of Ottawa Muslim Students’ Association (UOMSA) Film Festival in February.

The short film anonymously collects several stories of young Muslim women’s experiences of racism and shadism (discrimination based on skin tone) among their classmates, MSAs, friends, families, and even from community leaders in Ottawa.

The team behind the film are:

Ramla Said, is a Somali Canadian who is studying Biopharmaceutical Sciences. She’s been living in Ottawa since 2001.

Halima Abdisamed is also Somali Canadian. Studying International Development and Globalization, she was born and raised in Ottawa.

Sumaya Mohamed’s parents are both originally from Somalia. She is currently studying biopharmaceutical sciences with a specialization in medical chemistry and was also born in Ottawa.

Maryam Issa’s background is Yemeni-Ethiopian/Somali. She is studying Sociology with a minor in Psychology. She has been in Ottawa for almost 20 years.

Muslim Link interviewed the team behind the film on why they took this approach to explore a reality which Ottawa’s Muslim communities still find challenging to discuss head on. You can watch the documentary online below (It may take a few moments for the video to load from YouTube).

Why did you come together to make this film for the UOMSA Film Festival?

Ramla: A few of us made a video for the UOMSA film festival last year about converts, so we wanted to enter the competition again this year just for fun. The first topic that came to mind was racism within the Muslim ummah (global community of Muslims) and that’s when our motivation and passion set in. We recognized this was a heavy subject and very taboo but ultimately decided that it had to be done.

Halima: Anti-Blackness happens in everyday life on a micro/macro scale. Anti-Blackness in the ummah is a constant topic of discussion amongst us, so we finally wanted to back our words up with action.

Maram: We simply wanted to get out a narrative that is rarely ever discussed among Muslim leaders. We felt like it’s a taboo topic that the Muslim ummah as a collective shies away from. They do the absolute most to cover up and avoid dialogue and discussion [about it]; they do not want to acknowledge the fact that it is a serious and ramped [up] problem in our ummah.

When we try to bring up the issue of racism and anti-Blackness on social media platforms mostly Arabs and South or East Asians will respond with something along the lines of, “Yes, we need to address racism within our ummah but within the confines of our community and not publicly so that we don’t give more reason for Islamophobes to come after Muslims in this sensitive time…”

But the thing is, it’s been a problem since forever and Black Muslims have been addressing the issue and no one’s been listening and this just acts as another excuse to hush them.

If you really want to address and solve the issue, tackle it publicly! Spread the word, show solidarity and show care and commitment! When Islamophobes see that we are coming together as an ummah and solving our internal problems we come off as progressive and can actually end up giving good da’waah (spreading the word of Islam).

It says in the Quran,”Allah will not change the condition of a people until they change what is in themselves.” 13:11. We are taking the necessary actions that we can to be part of the change that we want to see in this ummah.

Why was it important to collect people's real experiences of racism for the film? Do you feel this helped to show the complexity of racist encounters within Muslim communities?

Ramla: We felt the best way to bring light to this issue was to share real life experiences that happened here in our own community in the hopes that some of these stories would hit close to home. In order to work towards change or even start some dialogue, we would have to first acknowledge that this is a real issue not only in our communities but globally as well.

Halima: It was important for us to collect the real stories of racism for the film because we knew we couldn’t be the only ones noticing the blatant racism, but we couldn’t predict how many people were receptive to the message of the video and willing to share their own stories with us. Anti-Blackness is a multi-tier issue, our goal was to tackle some of the most prominent tiers.

Sumayya: A lot of people like to think that racism doesn’t exist in our community but hopefully by hearing these stories of people who have encountered racism in the ummah, it can cause them to wake up and realize that this is a problem and it needs to be discussed Insh’Allah (God willing).

Maram: We felt it was important to show narratives of people from our own community, because unfortunately you don’t have to travel far to find racist and anti-Black experiences. They are happening within our own communities, in our own households. We’d like to make it clear that all these unfortunate experiences are true and not exaggerated in anyway, as some people have initially thought when they gave us feedback on some of the stories. We feel the need to stress this because this is an extremely toxic mentality, not only is it harmful and offensive, but it also contributes to the dismissiveness and erasure of the very real Black/people with darker complexion experience and struggle in this ummah; it feeds into the racism and anti-Blackness.

Your first story describes a young Somali woman’s encounter with a Muslim student who believes she is complimenting Somalis by distinguishing them from Black people from countries like Rwanda and Zimbabwe, who she seems to feel are inferior people.

In the film, you juxtapose these comments with images of Muslims in Rwanda during Eid. Why was it important for you to include this story? Why was it important for you to show that there are Muslims in Rwanda? How do you think we can challenge the idea that Black Africans, both Muslim and non-Muslim, are somehow “lesser” human beings within Muslim communities?

Ramla: This story was perhaps one of the most important in the film. It not only highlights anti-Blackness but shows there are levels to it. Somalis were complimented by basically being told that their ‘Arabness’ makes up for their ‘blackness’, when in reality we are not Arab nor do we associate as such. We are “Black-Black”, if you will, as is said in the story, not “Arab Black”. The images of Rwandan Muslims were shown to highlight that the “compliment” was actually quiet offensive and ignorant to the existence of our Rwandan Muslim brothers and sisters whom we share something very dear with; The Shahadah (Declaration of Faith for Muslims).

In the global context, it is Black Africans that are seen as lesser humans, but this disturbing mindset where one is valued based on their skin tone or outward appearance is exactly what Islam came to eradicate. This issue is so deep rooted that I cannot think of a feasible way to challenge this idea aside from learning and understand and living by the Qur’an sent down by Allah s.w.t. (May He (God) be Praised and Exalted) in hopes to rid ourselves of this disease of the heart-arrogance.

Sumayya: It was important for us to include this story because we wanted to show people that as Somalis we don’t see comments like those as compliments. But even more, as humans and Muslims, how can you think looking down on another or saying something hurtful to someone else would make another group of people feel better about themselves? It’s enraging to hear these types of comments because it stems from a place of arrogance and by Allah I have personally heard comments like these time and time again. It’s upsetting to see another human who is a Muslim (the slave of God, who is the Most Merciful and Just, the follower of Muhammed s.a.w (Peace and blessings upon him), who treated everyone with utmost respect) saying such disgusting vile things.

We juxtaposed this story with images of Muslims in Rwanda in order to show those who are watching our film that the people they so carelessly insult pray to the same God as them, they are equals. It’s sad that we have to show that people from Rwanda are also humans, and that some are our Muslim brothers and sisters who glorify the name of our beloved Creator. It’s sad that we have to remind Muslims we know of this, but it’s necessary.

In your second story, a young Arab woman discusses how her family sabotaged the marriage of her cousin to an Arab man who had a Black ancestor in his lineage. At one point her aunt says “I would rather lose my daughter than have her give birth to a Black baby.” Why was including this story important? Do you feel that young Muslims in Ottawa are struggling with their choices in marriage because of issues of race and lineage?

Ramla: This story is interesting; it shows that there isn’t only dislike in the black skin color but even its presence in lineage. This young woman planned to marry a man whose grandfather was Black. That would mean her child would be 1/8 Black, and it’s safe to say that you would probably not be able to see any physical signs to tell if this child had any sort of Black heritage. This shows to what extent Blackness is disliked in some communities.

In your third story, a young woman discusses having never seen her MSA raise funds for a Black African country over five years. Why did you think it was important to include this story? Do you think many people understand how this is actually an issue of racism?

Ramla: It’s important to include this story because it’s not the first time we’ve heard this, and the young woman discussing this is also not the first to have noticed it. Unfortunately, this is not only an MSA issue, this extends to some of our local mosques as well, and Islamic aid in general whether local or international. Some do not see this as a race issue but what is even more unfortunate is how, as believing Muslims, we are capable of being selective with our charity. It’s quite sad.

Halima: This story resonated with me the most because even in times of despair we are prioritized by our skin colour. People identify with pain more if it’s lighter, and the Muslim community isn’t exempt from that. As Black Muslims we are sought after to support our Brothers/Sisters in Islam, but support isn’t reciprocated. It was important to include that because a lot of people didn’t even realize that there wasn’t equal representation in our charities. It’s not like there is a lack of Muslims who are suffering in African countries.

Sumayya: We thought it would be important to add this story because we wanted to show that the community is not blind to the “unfairness” that is apparent in matters like charity and activism, especially the Black Muslim community that is often not given much attention to. There are so many Muslims that come from countries all around the world, and so the issues of Muslims are vast. If we do not take the time to properly address a range of these problems, many times, that leaves some parts of the community feeling neglected, and this breaks our unity. I think it’s quite clear how this can be interpreted as racism to some extent, because our community at large has demonstrated that not all Muslims are valued the same; even in giving charity this is obvious.

Most of your stories focus on the issue of anti-Black racism within the Ummah, but your fourth story explores the issue of shadism within South Asian communities, as a young Pakistani woman shares her experiences being perceived as darker-skinned and therefore as less attractive within her family and at South Asian community gatherings. Why was it important to include this story? Do you think the issue of shadism, which exists within a number of ethno-cultural communities, needs to be discussed more?

Ramla: This story was important because shadism, when exposed to it at young impressionable ages, can potentially be the seed that grows into racism. This issue needs to be discussed because it creates a complex in youth; they begin to dislike a darker skin tone for themselves and then they begin to dislike it in others as well.

Halima: People believing the darker you are the more inferior; this translates on a global level and on a community level. Shadism is the ugly-head of anti-Blackness a lot of the time. We see it in the Asian community where a lot of these bleaching creams are being manufactured, we see it in the African American communities, and various African communities, namely in the Somali Community, where a sign of showing someone you love them is calling them “Caadey” which translates to “Light”. As a community we need to ask ourselves: Why we are still letting this European standard of beauty continue to be our standard? And how do we make beauty more attainable and healthy for ourselves and our communities?

In your fifth story, a young Somali woman describes how her younger sister was told by her Turkish Muslim friend that they can no longer be friends because she is “Black and Bad”. Why was this an important story to include?

Ramla: This story shows that racism is not innate; this is something that is taught to children at ages too young for them to even understand the meaning of racism. It is very unfortunate that a 5 year old’s friendship was regulated based on skin tone.

In your sixth story, a young Nigerian woman discusses an experience in the Multi-Faith room at her university in Ottawa where an Arab woman asked her how she could read the Qur’an because she was Black. Why was it important to include this story?

Ramla: The Nigerian girl in the story actually wears hijab. We thought it was very funny but also disgusting that her Muslim-ness was questioned even while wearing the most symbolic item associated with Islam for women. And this was all because her skin tone just didn’t add up for this Arab woman. Islam belongs to Allah and it was brought down for all of mankind, not only one race.

Sumayya: The Arab woman in the story could not even believe the Nigerian woman was a Muslim, let alone able to read the Qur’an. We had to include this story so that those who are watching can see how questions like this are offensive because they are derived from a place of arrogance and pride that has no place in this religion.

In your seventh story, a young Arab woman with Black African lineage, discusses her experiences of anti-Black racism within her own family and from a respected community leader. Why was it important to include this story? Do you think it is difficult to discuss the ways in which racism can manifest itself even within families? Do you think it is important to address racism even if it comes from respected community leaders?

Ramla: This story shows that anything negative, if it can be associated with Blackness, will be [negative]. In this family even behavioural problems are said to arise from the “Black side.” Racism should be addressed whenever, wherever, regardless of how awkward the situation may get. There is a way of doing things and it should be done with the best of Akhlaaq (manners) especially when dealing with such a heavy subject.

Maram: In regards to people in authoritative positions, such as leaders and community members, people who are integral parts of our community, we’re taught in a cultural and religious context that the etiquette of dealing with elders is to be courteous and docile and always make peace. We have to be “respectful” even if the adult is in the wrong. We need to as a society overcome these practices of hushing and allowing for people to be toxic and harmful towards others in a space that is supposed to be a safe place for others. People will say, “They mean no harm,” or “It came from a place of humour...” There is absolutely no sense of humour in the situation. These are people in a place of authority who hold influence in our communities. There is absolutely no room in their job description to only be beneficial and cater to a certain demographic of people.

Many of these stories were quite emotional. Do you think it is important that Muslim communities better understand the impact on mental health that these forms of racism and shadism have on Muslim youth?

Ramla: Absolutely, this is not a part of our religion and if this type of negativity persists it could manifest into self hate which could lead to several different things including mental health issues. One may even mistakenly believe this is a part of Islam, and could end up leaving the religion all together.

Where do you feel this conversation needs to go in the context of Ottawa's Muslim communities?

Ramla: We need to be entirely more inclusive and welcoming of the Black Muslim population in Ottawa. We need to reach out and extend invitations, and let them know that we care about them as much as we care about their counterparts.

What do you hope readers of this article and those who watch your video do to address racism in the ummah?

Halima: This is advice to myself first: we need to dissect and understand the historical context of our thoughts; and how we could stop putting our brothers and sisters at a disadvantage in a race we are all trying to run.

Ramla: We know these stories are just some of the few that we were able to include while abiding by the time limit for the Film Festival. The support to make this video was overwhelming and each story was about upwards of 5-6 minutes which we had to cut down to 1-2 minutes. Some stories could not even be included and for sensitivity purposes a lot of content was cut out. If you think this is as bad as it gets, trust us when we say it gets worse.

The issue of anti-Blackness is very taboo and hard to listen to but it will not get any easier by ignoring [the issue]. It will be cringe-worthy and uncomfortable but it is necessary because this is something that affects the lives of some of our Muslim brothers and sisters on a day-to-day basis.

Just because you’ve never experienced it or seen it does not mean it doesn’t exist. We cannot dismiss the experience of others if we cannot see it due to our own privilege. We encourage all viewers and readers to attend any events that pertain to race relations within the Muslim ummah and if there aren’t any, organize them; we are more than happy to help.

I would like to conclude my point with a hadith:

Narrated An-Nu`man bin Bashir: Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) said, "You see the believers as regards their being merciful among themselves and showing love among themselves and being kind, resembling one body, so that, if any part of the body is not well then the whole body shares the sleeplessness (insomnia) and fever with it. Sahih al-Bukhari 6011

Sumayya: I just want people to focus on their manners in the way they treat and speak to their fellow human beings and their fellow Muslims. Our religion centres around perfecting our manners, and racism is against this way. I want people to reflect before speaking, think about those who they may hurt with their words. I want us as a community to move away from pride and arrogance because the Prophet s.a.w said “anyone with a mustard seed of arrogance shall not enter paradise”.

A Muslim is someone whose tongue another Muslim is safe from. Please, understand that your words need to be chosen and if you are battling with ego, then ask Allah to remove those feelings from you, because they are not from the teaching of our Prophet s.a.w, they are from the people of ignorance.

I know our Muslim community is filled with beautiful good people, and if I did not love and care for them, I would not talk about this problem. This is not an attack; this is an opportunity to draw nearer to Allah by leaving that which displeases Him s.w.t. It’s easy to say “We are one ummah” but now is the time to show it.

To view the video check it out on YouTube

This article was produced exclusively for Muslim Link and should not be copied without prior permission from the site. For permission, please write to info@muslimlink.ca.