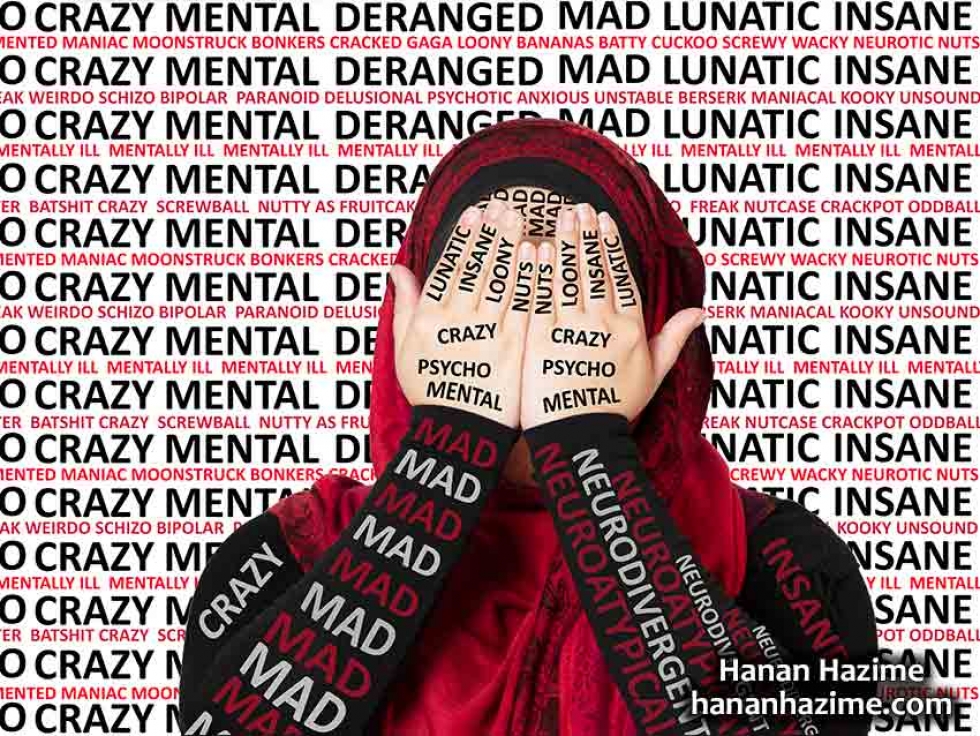

Hanan Hazime's piece "Psycho" is part of the "Labels" series where Hanan explores how she is labelled by others because she is a visibly Muslim woman living with a mental illness.

Hanan Hazime

Hanan Hazime's piece "Psycho" is part of the "Labels" series where Hanan explores how she is labelled by others because she is a visibly Muslim woman living with a mental illness.

Hanan Hazime

Feb

The Mad Muslimah: Using Art to Challenge the Stigma of Mental Illness

Written by Chelby DaigleLebanese Canadian writer, visual artist, and arts educator Hanan Hazime has been using visual art to challenge the stigma associated with being someone who lives with a mental illness.

In 2019, her conceptual art series "Labels", printed on satin fabric, was showcased at the annual Workman Arts' Rendezvous with Madness Festival, the largest arts festival exploring themes of mental health and addiction in the world. "Labels" is made up of three pieces "East vs. West", "Femininity" and "Psyho" where Hanan explores the ways she is labelled by the world as a Lebanese Muslim, as a woman, and as someone living with mental illness.

As an arts educator, Hanan also had the opportunity to teach patients at the Mood and Anxiety Unit and the Integrated Rehab Unit of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, to use everything from watercolours, pastels, and acrylic paints to create mixed media art pieces from collages to found poetry to express themselves.

Muslim Link interviewed Hanan Hazime about her experiences as a visibly Muslim female artist who faces both the challenge of living with a mental illness but also of coping with the sometimes violent forms of Islamophobia visibly Muslim women are often exposed to daily, and which ultimately has an impact on our mental health.

How did you feel when you first were diagnosed with a mental illness? What has been the impact of this diagnosis on your life, visual art and writing?

I felt relieved because (ironically) the diagnosis meant I wasn’t “crazy” or “losing my mind” after all —it was like "oh, I guess there are actual physiological and neurological causes for what I’ve been experiencing".

“What’s wrong with me?” is a question that had been haunting me since adolescence. The diagnosis made me see that nothing is “wrong” with me: my brain functions differently than a neurotypical brain and that’s okay. Everything I’d been through made so much more sense when I was able to think about it in terms of biology and neuroscience. Sometimes, the neurons in my brain misfire and my serotonin/dopamine levels are out of wack and there is far too much cortisol in my body but at least, I know what’s going on now.

The diagnosis allows me to put my lived experiences into words. It’s much easier to write and make art about mental health challenges like intrusive thoughts and disassociation when you have concrete words to describe such experiences. The biggest impact the diagnosis has had is it that it has allowed me to connect with other people (especially other artists) who have also faced mental health challenges. At first, I felt like I had to hide the diagnosis but the more people I encountered who were also psychiatric consumers/survivors, the less alone I felt and eventually, it became easier to rip the sanity mask off.

What issues around mental illness are you trying to explore in your art (visual and written)?

Some of the biggest issues around mental illness are stigmatization, and sanism/ableism There’s a lot of misinformation and misunderstandings surrounding the topic. Through my art, I’m hoping to dispel stigmas and stereotypes, and empower folks with mental health challenges. I hope to question binaries; binaries are a classification system consisting of two categories such as good vs. evil, light vs.dark, sane vs. insane. It doesn't take into account that some realities might exist on a more nuanced spectrum. It doesn't recognize the gray areas of life. Mental illness isn’t some bogeyman hiding in the dark. According to the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA), 1 in 5 people in Canada have personally experienced a mental health problem or illness. Mental illness can affect anyone regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, socio-economic class, education level or religion. It’s time we stop brushing mental health issues under the rug. Through my art, I want to show the world that folks with mental illness are humans like everyone else. We have families, we have careers, we have interests, passions, and hobbies, we have dreams and goals, we fall in love, we get our hearts broken. Our mental health does not define us.

Your work was exhibited through Workman Arts in 2018. Could you tell us about how this opportunity arose and what you have taken away from the experience?

Workman Arts is a wonderful organization that supports artists with lived experience of mental health and/or addiction issues. They provide professional art classes, artistic development workshops, exhibition opportunities, and much more. I’ve been an active member of Workman Arts since 2016; I was their 2017-2018 Writer-In-Residence during which I facilitated a year long Experimental Literature course. My visual artwork has been exhibited at their annual Being Scene art show since 2017.

Every year in the Fall, Workman Arts hosts the Rendezvous with Madness Festival and in 2018, I had the opportunity to exhibit my art during the festival at the Bursting Bubbles Exhibition which was curated by Claudette Abrams. It was an amazing experience because all the feedback I received about my art was incredibly positive. The three pieces from the "Labels" series that were showcased are 42” x 60” self-portraits printed on fabric. When I saw them hanging at the Toronto Media Arts Centre, I got a bit nervous. I am an introvert so I don’t like being the centre of attention, yet, here were three enormous blown-up images of my face overlaid with what some might consider controversial texts. One of the portraits had words like “psycho” and “insane” literally emblazoned on my body. However, there was no need to worry because everyone I spoke to loved the pieces and had lots of great things to say about my work. The pieces really resonated with folks. The experience encouraged me to be my authentic self.

I will continue creating art that will shatter binaries and dispel stigmas/stereotypes.

You also have worked as an arts educator, in come cases with other people living with mental health issues? Tell us about those experiences.

My primary mission as a multidisciplinary community arts educator and creative writing facilitator is to provide accessible and inclusive arts education to marginalized communities with a special focus on crafting safe spaces for BIPOC individuals with mental health challenges and Muslim youth to discover and enhance their creative skills. My hope is that through their writing and art, these marginalized voices will be amplified and empowered.

I have extensive experience facilitating, instructing, and organizing a variety of creative writing and multidisciplinary arts workshops and arts related events for a diverse range of communities. As a member of the TWC (Toronto Writers Collective), I have facilitated many fiction and poetry writing workshops across Toronto. Because the aim of the TWC is to empower marginalized voices, I have had the opportunity to work with various marginalized groups at community centres such as Mustard Seed and Women’s Health in Women’s Hands. I’ve also worked with Toronto’s East End Arts as poetry workshop facilitator for their Art MEETs series.

In the summer of 2017, I received a $5000 grant from ArtReach to develop, organize, and facilitate Poetry ReRooted: Decolonizing Our Tongues, a multilingual creative writing workshop for Muslimah youth. At the end of the workshop, I compiled, edited, and published a poetry chapbook for the workshop participants and assisted them in organizing a chapbook launch and poetry night. I have also hosted a multilingual poetry workshop for BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Colour) youth at the Margin of Eras Gallery with the support of CUE Art Projects.

I was the 2017-2018 Literary Artist in Residence and Literary Arts Instructor at Workman Arts. In addition to working on my own writing, I provided mentorship to aspiring, emerging, and established writers at Workman Arts. I also taught an Experimental Literature course in which we explored various writing techniques using both poetry and prose. I co-designed and facilitated a ten-week multidisciplinary arts workshop series for the 2018 Arts and Minds: A Community Art Series in collaboration with the Neighborhood Arts Network and Workman Arts. The workshops culminated in an arts exhibition at the Aga Khan museum in January 2019. I am currently working as a freelance multidisciplinary arts instructor for the Art Cart program at CAMH, and as an Art Appreciation coordinator at Workman Arts where I plan and organize accessible, and free (or low cost) art related trips/events (i.e. trips to galleries, museums, theatre shows, etc.) for Workman members.

How do you feel your experiences of Islamophobia have impacted your mental health given that you have a mental illness, and/or has your experiences of Islamophobia also intersected with your experiences of sanism (discrimination against people living with mental illness) ?

The violence enacted towards me by Islamophobes has definitely impacted my mental health. On more than one occasion, I have been nearly run over by Islamophobic drivers while crossing the street. After yelling obscenities at me, one of these bigots said he wanted to kill me because I’m a “terrorist.” Another just sat in his SUV and maniacally laughed after hurling racist insults at me. I’ve had liquids thrown at me from moving vehicles. I’ve been verbally harassed on countless occasions as well. A man actually came up behind me on the escalator in the Eaton Centre and threatened to kill me because I’m Muslim. These types of incidents exacerbate my anxiety and make me feel unsafe in public.

I spoke to a therapist about my encounters with Islamophobia once. I had said that in addition to my own lived experiences, after hearing of hijabi women being pushed off of subway platforms or being brutally beaten up on public transit, I felt anxious commuting by myself (especially at night time) because I was afraid I could get hurt. We were doing cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and the therapist kept telling me to “challenge my thoughts”. She claimed that I was just being paranoid and that I wasn’t in any danger. You cannot “challenge” thoughts when those thoughts are rooted in reality. I wasn’t having delusions. It’s unfortunate that the anxiety caused by the trauma I’ve endured from Islamophobia is often dismissed as just irrational fears by non-Muslim mental health professionals. Commuting by myself isn’t always safe, especially when there’s a major surge of Islamophobia in the media. This is a fact, not an unfounded fear. If an individual who claims to be “Muslim” commits an act of mass violence then there’s immediate backlash and it’s taken out on visibly Muslim woman because we’re a clear target.

If the individual isn’t Muslim or otherwise racialized, they are automatically labelled as “mentally ill” even if they are not and that further perpetuates the stereotype that mentally ill people are violent. In fact, many studies have shown that people with mental illness are more likely to be victims of violence. There’s a reason we use the term psychiatric survivor. The mental health system is full of abusive professionals and predators. Also, society in general is quite sanist — especially if you have a less palatable (less socially acceptable and easy to relate to) diagnosis like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Living as a mentally ill Muslim means you have to deal with both Islamophobia and sanism. Beyond the daily harassment and microaggressions I’ve experienced from individuals, the intersectionality of my two marginalized identities have translated into difficulty securing employment, housing, and other important resources on a systemic scale.

Currently, although there is talk about the impact of Islamophobia on mental health, these conversations often exclude those of us who lived with diagnosed mental illnesses. What work needs to be done by both Muslim and non-Muslim organizations to support Muslims with mental illnesses who experience Islamophobia?

The main course of action that both Muslim and non-Muslims organizations should take to support Muslims with mental illnesses who experience Islamophobia would be to INCLUDE these folks in their organizations. Representation is vital. Invite Muslims with mental illness to sit on boards and committees, have them be actively involved in the organization. Listen to what they have to say and what their needs are. If you do invite us to speak to your organization, make sure we are receiving adequate compensation for our time - whether it is monetary or through an energy/service exchange, we deserve to be paid for our labour. I cannot speak for all Muslims with diagnoses of mental illnesses who have experienced Islamophobia but I believe that the bulk of the work lies in giving us a voice and allowing us to freely express our concerns.

There is a growing movement among those of us who live with diagnosed mental illnesses to reclaim the world "mad". You have used the word "mad" in reference to your art work on this subject. Why?

Terms like “mad” or “psycho” or “insane” can conjure a lot of negative connotations or even be weaponized to hurt people who have a mental illness so I am actively reclaiming these labels to give them a more neutral or even positive meaning. I personally dislike using the term “mentally ill” to describe my lived experiences as I feel like that term is much too pathological. Ultimately, despite what labels or “diagnoses” I have been given by physicians/psychiatrists, those clinical terms which are so neatly packaged and at times abbreviated aren’t enough to encompass the full breadth of my struggles, my suffering, my resilience, and my journey towards wellness and healing. I am proud to be mad/neurodivergent!

What would you like to do next with your exploration of "madness" in your visual art?

I would like to create an artwork series that explores PMDD (premenstrual dysphoric disorder). Many people have heard of PMS (premenstrual syndrome) but PMDD is not well known. In fact, researchers don’t know for sure what causes PMDD. It is believed that hormonal changes throughout the menstrual cycle may play a role in altering brain chemicals like serotonin levels. It is astonishing to me that an illness which affects “up to 8% of women” (according to the Mood Disorders Association of Ontario) is lacking in research. The condition is predominately associated with severe psychological symptoms as well as physical ones. The symptoms which usually start seven to 10 days before menstruation and decrease within a few days of the onset of menstrual flow can include anxiety, suicidal ideation (suicidal thoughts), extreme mood shifts, depression, difficulty concentrating, fatigue, insomnia, feeling out of control, increased irritability as well as breast tenderness, headaches, joint/muscle pain, and bloating. Many females endure this condition in silence because of the stigma around menstruation. I’m hoping to create some visual art that will bring awareness to those of us who are suffering though PMDD every month.

If people want to connect more with your work beyond following you on social media or your website, what opportunities do they have?

My visual arts series "In Red" which which aims to challenge cultural binaries, labels, and identities imposed on Muslimahs is being exhibited at the 2020 Feminist Art Festival in March in Toronto. This year's theme is Narrative Healing, I will also be speaking on a panel during the festival about my experience with defining space across colonial borders through fragmentation, representation and visibility.

My paper collage piece "Dissociation" which was featured at (mus)interpreted's 2019 exhibition will be showcased at this year's Being Scene exhibit in March. The collage explores pathological dissociation versus non-pathological dissociation through the use of colours and shapes.

In addition to my visual artwork, thanks to an OAC (Ontario Arts Council) grant, I am currently working on my first novel. The novel is a coming-of-age story which explores the struggles of Zaynab, a Lebanese- Canadian Muslimah who is trying to navigate the challenges of adolescence while also dealing with mental illness. I'm hoping to complete and publish the novel this year so that it can be a source of hope and inspiration for young Muslimahs who might be going through similar experiences. It's the novel I wish I had as a teenager.

To learn more about Hanan Hazime:

Visit Hanan Hazime's Website

This article was produced exclusively for Muslim Link and should not be copied without prior permission from the site. For permission, please write to info@muslimlink.ca.