Political dignitaries attend the funeral for three of the six victims of the Quebec City mosque shooting in Montreal in February 2017.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Paul Chiasson

Political dignitaries attend the funeral for three of the six victims of the Quebec City mosque shooting in Montreal in February 2017.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Paul Chiasson

Jan

A year later: The mosque massacre & rising Islamophobia

Written by Tarek YounisOn Jan. 29, 2017, a man entered a Québec mosque during evening prayer and opened fire on the backs of 53 congregants. Six died immediately.

A funeral service was held at a Montréal hockey arena for three of the victims. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, Québec Premier Phillippe Couillard and other dignitaries delivered heartfelt speeches. They affirmed that an injustice towards Canadian Muslims is an injustice towards all Canadians. Muslims are Canadians and their pain is our pain, the politicians exclaimed.

“Vive le Québec! We love Canada!” the stadium replied.

One year later, it’s time to look back at the funeral and listen carefully to what was said. Why affirm the Canadian-ness (and Québecois-ness) of grieving Muslims?

It couldn’t possibly be to discourage the public from Islamophobia. That would be like declaring “Don’t be racist” — futile.

Rather, their declarations were directed at Muslims across the country: Don’t let this brutal act persuade you into thinking you don’t belong. The views of the accused killer, and others like him, are wrong. Muslims do belong to Canada and Québec.

Ultimate expression of Islamophobia

Imagine public attitude towards Muslims on a continuum, however. On one end, we find the mass murder, the ultimate expression of anti-Muslim sentiment. On the other, we find the loving embrace of Muslims as our own, like a family welcoming an adopted child.

When growing anti-Muslim sentiment —no thanks to politics — resulted in a massacre, the political good will at the funeral accomplished one thing: It reminded Muslims that they do, in fact, belong to Québec. Their speeches therefore never escaped the continuum’s trajectory.

Rather, political declarations of solidarity — well-intended as they may be — remained fixed on what American scholar Anne Norton calls “the Muslim question,” a reference to Karl Marx’s On The Jewish Question.

“The Muslim question” defines the political centricity of Muslims as the archetypal threat to democratic nation-states. It’s the thematic summation of all moral panic surrounding Islam and Muslims, from civic integration to the war on terror. In short, the Muslim question is the inevitable “othering” of Muslims as foreign entities within the national body.

The politicians did not unpack the Muslim question at the funeral; they did not bring to our attention the unremitting oscillation between “good/accepted” and “bad/rejected” Muslims on the aforementioned continuum.

They simply positioned themselves favourably along its path. In doing so, the politicians legitimized the continuum’s raison d'être: The moral panic surrounding Islam and Muslims.

Moral panic

Their statements catered to the tacit anti-Muslim attitudes endemic in society, where Muslims are perceived as integration-resistant and threatening. They might as well have exclaimed: And as to the eternal question of whether Muslims belong in this country, Muslims are Canadians!

It should come as no surprise, then, that the niqab reappeared in the political limelight with Bill 62, Québec’s Religious Neutrality law.

The sentiments shared at the funeral remain relevant as the niqab is hoisted, once again, as the symbol of religious defiance of secular sanctity.

Our inability to question why Muslims have come to represent the “other” shows how little we are able to manoeuvre in our discussion. Bill 62 is the perfect example of this. The sensationalizing of a societal non-issue — niqab-wearing women who number perhaps no more than a few hundred in Québec — took centre stage only months after we’d buried the victims of the mosque massacre.

Political gestures of solidarity are comforting, but they remain fixed within the parameters of the Muslim question.

The root causes of why we’re asking the Muslim question run deep within the fabric of a society interlaced with financial, political and existential insecurities. And politicians continue to campaign on platforms that pander to the Muslim question — because it works.

The moral panic is real; it elected Trump.

Moving forward, if we are to make any progress, Canada and other countries must tackle the issues underlying the perception of Muslims in public consciousness.

Directly combating discrimination has proven to be insufficient. We cannot allow Muslim representation to oscillate incessantly. We cannot persist with the irony of proclaiming: “Don’t hate Muslims … but the niqab poses a national concern.”

Not an outlier

The accused killer was not a racist outlier. Racists are the product of the Muslim question somewhere along the end of the continuum where all Muslims are unequivocally bad/rejected .

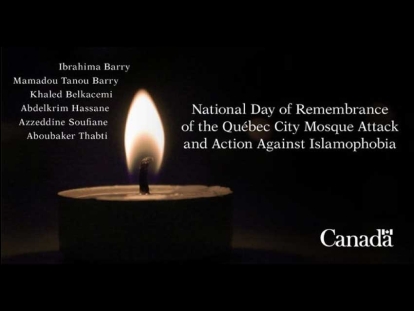

What have we learned from the Québec City shooting a year ago? Very little, it seems. At the time of this writing, Québec political parties have refused to acknowledge Jan. 29 as a National Day of Remembrance and Action on Islamophobia.

The Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) says “[the shooting] is the intolerable act of a single person and not that of an entire society. Québecers are open and welcoming, they are not Islamophobic.” And yet Québec City anti-Muslim hate crime doubled in 2017.

![]() The 29th of January should serve as a reminder then that we are — to this day — still trapped in the Muslim question’s awful continuum.

The 29th of January should serve as a reminder then that we are — to this day — still trapped in the Muslim question’s awful continuum.

Tarek Younis, Newton International Postdoctoral Fellow, UCL Division of Psychiatry, UCL

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.