Oct

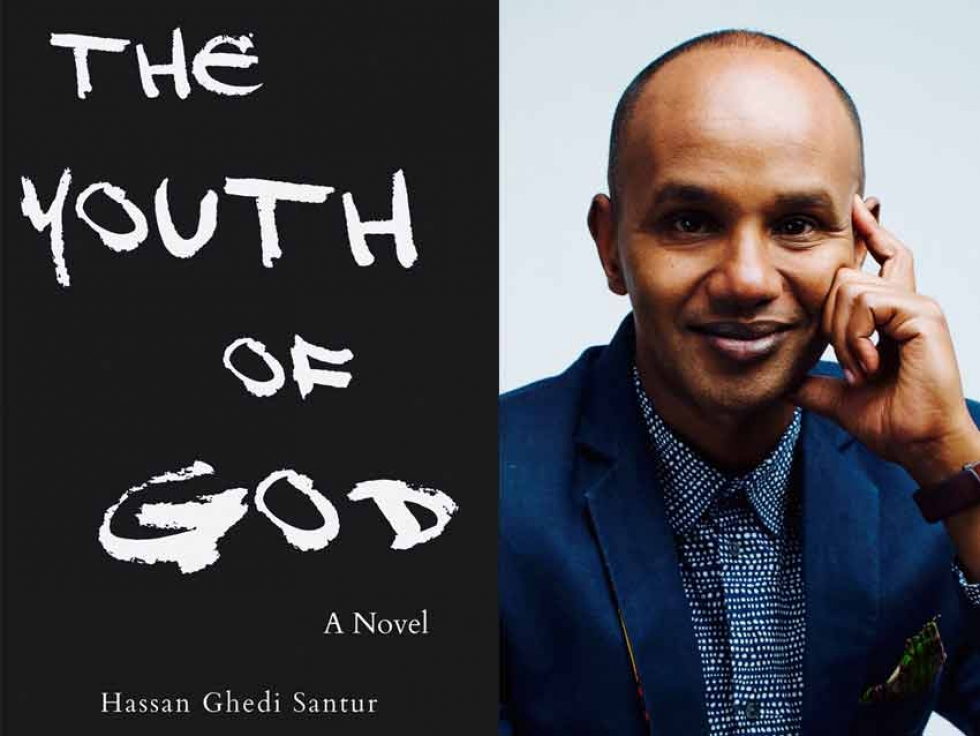

Somali Canadian Journalist Hassan Ghedi Santur Latest Novel Explores Radicalization of Muslim Youth in Toronto

Written by Chelby DaigleSomali Canadian author Hassan Ghedi Santur's latest novel, "The Youth of God", published by Mawenzi House, follows a Muslim teen in Toronto as he struggles with his education and his faith.

Hassan Ghedi Santur emigrated from Somalia to Canada at age thirteen. He has a BA in English Literature and an MFA from York University, and an MA from Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. He has worked as a radio journalist for CBC radio and his print journalism work has appeared in the New York Times, Yahoo News, and The Walrus, among others. In 2010, he published his debut novel Something Remains, followed by Maps of Exile, an exploration of the plight of African migrants in Europe.

As described by Broken Pencil, "In stark prose, Toronto-based writer Hassan Santur explores the Somali-Canadian experience through the eyes of two characters: First, there’s Mr. Ilmi, a passionate Mogadishu-born high school teacher trapped in an uncertain marriage, the result of an arranged union. Then there’s his student Nuur, who knows only the grey suburban towers where he and much of his community lives. Nuur is a devoted Muslim, bullied by his peers (and his itinerant father) for his beard and traditional dress. Mr. Ilmi sees potential in the young man, but so does the radical Imam Yusuf of Nuur’s mosque. "The Youth of God" is a brave novel that lays bare the complexity and pull of extremism."

In an interview with CBC, Santur explains why he decided to write a novel about the radicalization of a Somali Canadian youth from Toronto: "The literal translation of al-Shabaab is 'the youth.' I've done a lot of research about the history of the group and how they portray themselves and the function that they think they serve. They see themselves as the youth that is representing God's will or God's wishes. I found it interesting that they see themselves as the representatives of God. Back in 2012-13, when I started writing the novel, there were stories in the news about young Somali kids who were indoctrinated and radicalized in various parts of Canada and were sent to Somalia to fight for al-Shabaab. One of the articles I read said that 20 young men may have gone to fight for al-Shabaab through this particular way of slowly being radicalized, slowly being indoctrinated. I was curious as to why a young Somali kid who's never even been to Somalia would be compelled to leave the only life they've ever known in order to fight for this organization in a faraway land. I was working backwards and trying to find potential answers for why something like that would happen. A lot of the stories had one particular theme that was running through them: a sense of alienation, a sense of feeling like they don't fit in, they don't belong. That sense of alienation makes the idea of finding a home — sometimes a literal home and sometimes an emotional home — quite attractive to these young men. It can give them a sense of identity and a sense of belonging in the world."

As a journalist, Santur has written about young men who have defected from Al-Shabaab as a Pulitizer Center grantee. He discusses this research in the video below (It may take a few moments for the video to load from YouTube).

In an interview with Broken Pencil, Santur discusses how he drew from his own experiences when writing "The Youth of God", "There is a bit of me in both Mr. Ilmi and Nuur. Mr. Ilmi came to Canada at around the same age as I did, in his early teens. He has vivid memories of his early life in Somalia—even his trip back to Mogadishu and his attempts to find his childhood home, which was completely destroyed by the war, mirrors my first trip back to Mogadishu in summer of 2012 when I went there to make a two-part radio documentary called “Things We Lost In the War.” There are also bits of me in Nuur. When I was a teenager and new to Toronto, the sense of alienation and differentness I felt is quite similar to what Nuur feels. And, like Nuur, books became a refuge and a way to make sense of the new world around me."

Read an Excerpt from "The Youth of God": "Ever since his father left and took a second wife, Nuur had come home from school to find his mother Haawo usually still in her baati, the long, formless cotton dress that she loved to wear to bed. She would be sprawled on the overstuffed olive-green living room couch, talking on the phone with one or more of her three sisters who were scattered around the world. Her calling card gave her five hundred talking minutes for just ten dollars, and she went through several cards a week. These two- or three-way calls spanned the globe, with his Aunt Jamila in Stockholm, Aunt Zaynab in Dar es Salaam, and Aunt Luul (his favourite) in Dubai. They consoled her and also admonished her for still crying over the man who had discarded her. The one who could be relied upon for admonishment was Aunt Luul. She was the strongest and feistiest of them, a no nonsense feminist who would be horrified, however, to be described as one. For her, a feminist was synonymous with a lesbian." You can read more from the novel on Open Book here.

Buy "The Youth of God" online here

This article was produced exclusively for Muslim Link and should not be copied without prior permission from the site. For permission, please write to info@muslimlink.ca.