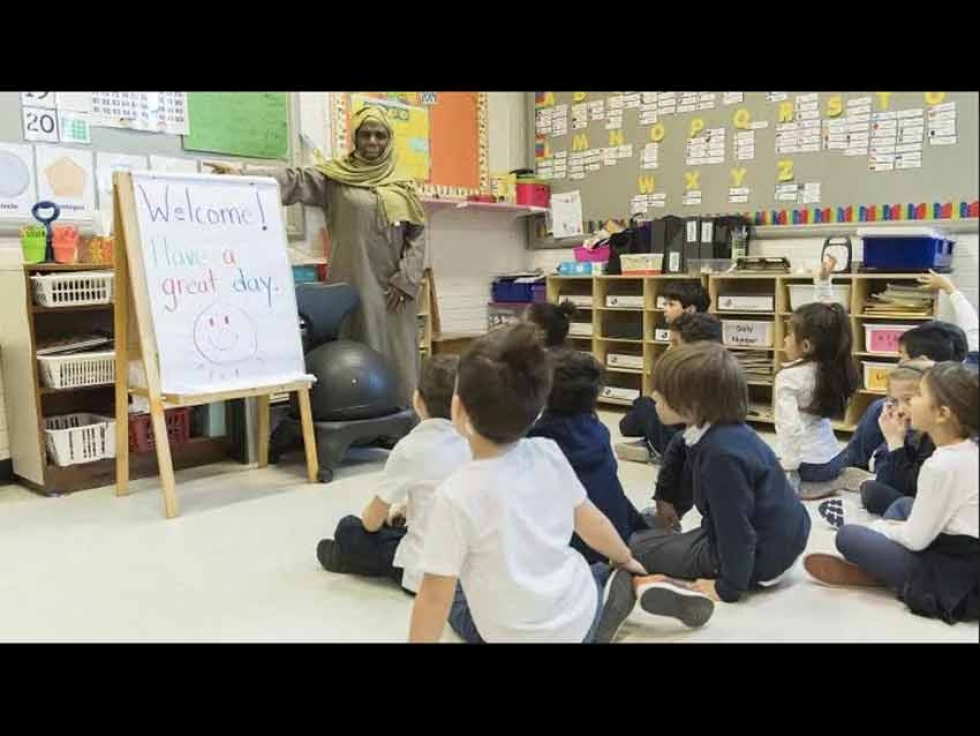

English Montreal School Board (EMSB) teacher Haniyfa Scott gives a lesson to her kindergarten class in April 2019. The EMSB is challenging the CAQ government's secularism law, which bars newly hired teachers and school administrators from wearing a hijab or any other religious symbol.

Graham Hughes/The Canadian Press

English Montreal School Board (EMSB) teacher Haniyfa Scott gives a lesson to her kindergarten class in April 2019. The EMSB is challenging the CAQ government's secularism law, which bars newly hired teachers and school administrators from wearing a hijab or any other religious symbol.

Graham Hughes/The Canadian Press

Mar

Canadians Are Entitled to Legal Help to Protect Their Charter Rights: The English Montreal School Board and Quebec's Bill 21

Written by Anne LevesqueThe Court Challenges Program was at the heart of the latest scuffle between Ottawa and Québec. The program provides financial support to Canadians seeking to assert their constitutional language and human rights before the courts.

Upon learning that the program provided federal funding to the English Montreal School Board to challenge the province’s religious symbols ban, Premier Francois Legault accused Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of “insulting” Québecers.

Based on my work on public interest litigation, I believe Legault’s concerns are unfounded. Rather, the funding provided by the Court Challenges Program breathes life into rights guaranteed by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Studies have shown that Canadians overwhelmingly support the Charter. But Charter rights are hollow if they can’t be enforced.

Supporting the Charter therefore means supporting the Court Challenges Program. It is, in fact, the unsung hero behind many of the most significant human rights advancements achieved in our country. That includes the challenge to the retrofitting of Via Rail’s inaccessible cars, the the recognition of the rights of same-sex couples and the protection of publication bans that shield the identity of sexual assault complainants.

Guards against unconstitutional laws

It prevents unconstitutional laws from remaining on the books simply because individuals whose rights are violated don’t have the means to challenge them.

Because many don’t. The cost of asserting Charter rights is prohibitive. Recent studies estimate the average cost of a one-week trial in Canada is more than $50,000. Constitutional challenges often involve particularly complex legal issues and extensive evidentiary records.

By way of example, a recent language rights trial in British Columbia lasted 238 days, involved more than 40 lay witnesses and 13 experts, 1,600 exhibits and more than 1,000 pages of written arguments. It is simply inconceivable to expect anyone to spend this much money or time to assert their rights.

At first glance, the idea of using public funds to sue the government may seem counter-intuitive. That’s an opinion commonly expressed by those who oppose the Court Challenges Program.

After Stephen Harper’s Conservative government cut the former program in 2007, former cabinet minister John Baird said he didn’t think it “made sense for the government to subsidize lawyers to challenge the government’s own laws in court.”

But concerns regarding wasteful government spending on lawyers are misdirected. People seeking to assert their Charter rights often go up against large taxpayer-funded legal teams who fight them tooth and nail.

A drop in the bucket

In fact, the Department of Justice that represents the government of Canada in most of its legal matters often refers to itself as “Canada’s largest law firm.” The Court Challenges Program’s $5 million annual cost is a drop in the bucket compared to the $717.9 million spent annually by the Department of Justice.

It would be a gross exaggeration to say that the program levels the playing field between individuals seeking to assert their Charter rights and governments that oppose them. It does not. Governments routinely spend millions of dollars fighting individuals and groups who challenge what they allege to be unconstitutional or discriminatory laws or polices.

Just ask Cindy Blackstock. She is the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society who, along with the Assembly of First Nations, filed a historic human rights complaint against the government of Canada for its discriminatory treatment of 165,000 First Nations children.

As detailed in my recent paper regarding the history of the complaint, the Caring Society was represented by pro bono counsel, while the government spent at least $8 million in legal fees fighting the case. The case illustrates just how much money governments are willing to spend to fight to defend their laws and policies, even when they know they are discriminatory.

The Court Challenges Program provides individuals with only a fraction of what governments spend to fight them. Until governments are prepared to put caps on what they spend in legal fees fighting Charter cases, the program is one way to slightly reduce the significant power imbalance that otherwise exists in the courtroom.

Why provide federal funding?

The English Montreal School Board was offered funding from the program to challenge the Québec religious symbol ban based on educational rights guaranteed under the Charter. But why should the federal government get involved with education given it’s a provincial matter?

Because under the Official Languages Act, the government of Canada has a duty to enhance “the vitality of the English and French linguistic minority communities in Canada” and to support and assist their development.

The Court Challenges Program is one way Canada fulfils this obligation. The funding of provincial cases, and specifically those relating to education rights, are particularly important in the context of official language minority rights.

The Supreme Court of Canada has emphasized the vital role of education in preserving and encouraging linguistic and cultural vitality. Minority language instruction rights are what give meaning to all other language rights protected in the Charter. Put more simply, the right to use one’s official language when communicating with government institutions would be meaningless if no one had been educated to speak or read in that language in the first place.

Accordingly, the program supported important cases such as Mahé vs. Alberta, which recognized the right to management and control over minority language facilities and instruction, and Arsenault-Cameron vs. Prince Edward Island, which clarified that this right includes the power of communities to determine the optimal location of their schools.

It’s unfortunate that the current program doesn’t provide funding for members of equality-seeking groups. I co-authored submissions for the Council of Canadians with Disabilities to the parliamentary committee tasked with making recommendations on the structure of the new Court Challenges Program. In those submissions, I urged that funding should also be provided for provincial cases alleging violations of Section 15 of the Charter, which guarantees the right to equality.

I argued that discrimination against people with disabilities commonly occurs in provincially regulated areas such as education, health, social services, income maintenance and housing.

And so including funding for provincial cases would better meet the needs of historically disadvantaged communities protected under the Charter.

So did Trudeau insult Québecers?

A few clarifications are in order.

Firstly, Trudeau did not prompt the English Montreal School Board to challenge Québec’s religious symbols law by financing their litigation.

The Court Challenges Program is managed independently, and decisions regarding whether and how funding is allocated are made by expert panels who do not report to government. The federal government has no involvement.

Secondly, Charter challenges are not an insult or a threat to citizens. Rather, they’re a sign of a healthy and strong democracy in which governments are held accountable and minorities are endowed with the means necessary to maintain and promote their identities against the assimilative pressures of the majority.

The Québec premier has repeatedly said he’s confident his law is constitutional. If so, he should welcome the opportunity to have courts weigh in on the matter.

Instead, the Montreal English School Board declined the money after Legault politicized the program.

It is hoped that other groups won’t follow suit. It is bad enough that those seeking to assert their Charter rights must face off against large teams of government-funded lawyers in court. They shouldn’t also be bullied into turning down money aimed to levelling the playing field. Otherwise, there will be nothing stopping governments from passing unconstitutional laws because citizens won’t be able to challenge them.![]()

Anne Levesque, Assistant professor, Faculty of Law, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.