Films screened at the 2018 Mosquers Film Festival in Edmonton, Alberta.

Films screened at the 2018 Mosquers Film Festival in Edmonton, Alberta.

Dec

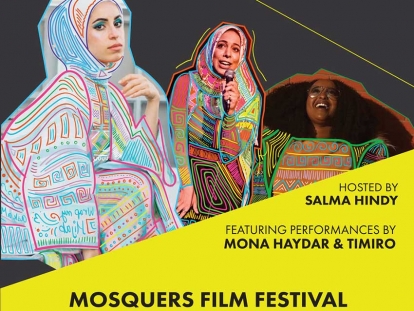

The Mosquers: Edmonton's Annual International Muslim Film Festival

Written by Aicha LasfarEdmonton is a city with a small town reputation, and yet it is home to North America’s one and only Muslim Film Festival.

In 2006, a small grassroots organization naming themselves “The Mosquers” launched an event at the University of Alberta in Edmonton where local Muslim youth were invited to tell their stories through film. The festival became a success, but was mostly attended by the local Muslim community.

Now in 2018, the Mosquers have evolved to showcase films submitted from all around North America and the world. This year, the festival was a red carpet event hosted at the Winspear Centre in downtown Edmonton, complete with an after-party and entertainment by renowned artists such as Brother Ali and Omar Regan. The evening also featured a visual art gallery and opened with a ceremony acknowledging the local indigenous community.

Muslim Link got in touch with the chairman of the Mosquers board, Sikandar Atiq to learn more about the history of the film festival and where it is headed in the future.

Firstly, can you tell us about yourself and your personal history with the Mosquers?

I grew up in Edmonton and went to the University of Alberta. My professional life is very different from my Mosquers life; I work in finance but I was involved in the Mosquers from year one. I was very amateurishly submitting films with the festival for a lot of my university years.

I moved to New York in 2012 for my Masters in Business Administration and it was there that I first met a lot of creative Muslims which is not something that I had seen before. Growing up in Edmonton in a more traditional and conservative community, you don’t really have a lot of creatives in the Muslim community.

In New York, it was the first time I saw people who were musicians, graphic designers, videographers, photographers , writers and poets. All of these people had carved out a profession and a niche for themselves with a very clear understanding of how their faith has influenced their art form.

How did this new knowledge influence your involvement with the Mosquers?

When I moved back to Edmonton in early 2015, I was approached by the team at the Mosquers [to join their board]. I loved the platform, I loved the event per se but I was bummed out at the level of competition and the level of quality that we were displaying to people.

Not to take anything away from the people who were presenting films at the time; I feel very strongly about encouraging local filmmakers to grab a camera and tell their story, but if we’re trying to use this as a platform to bring people of all faiths and backgrounds together, the quality of the art has to be at a level where it can get people excited.

I saw stuff in New York that got people excited. It’s more so about the idea that there are really creative people in the Muslim community all over the World, and it should be our job to unearth them and make it known to them that this platform exists for them, and to use it.

How did the Mosquers emerge from the University of Alberta and what was their mission?

The idea came about to encourage young Muslims to tell their own stories rather than allow the media to do it for them. Let’s encourage them to grab a camera and tell their own story; that’s how it began - as a very grassroots community driven event.

The first event was completely for free. It was on a stage in the middle of the cafeteria in the student union building. It was a massive success, hundreds of people showed up with great community support.

It was a nice halal night out for families of the Muslim community, but I was starting to see was that we were losing sight of the original intention which was to showcase these stories to non-Muslims, and for me that was the most important element of what we could accomplish.

We made a very conscious shift in 2015 to bring the attention back to what the purpose of the was. That meant that we needed to increase the quality of the filmmaking. It’s very difficult to bring a large contingent of the general public to an event and get excited about films that are of poor quality.

Another big thing that we tried to do was to recognize that, even within the Muslim community, there’ a lot of diversity and there’s a lot of requirement for bridge building.

We had a big and lofty intention of building bridges between the Muslim community and the non-Muslim community, but just as importantly for me is building those bridges within the Muslim community.

We spent a lot of time talking to the Ismaili community, the Shia community and talking to different ethnic backgrounds within the Muslim community because we wanted to make sure that everyone of those groups felt that this was a platform that was as much for them as it is for the Pakistani Sunni Muslim who has felt like this was their event since day one.

What is the criteria for films submitted and the selection process like?

At first it was just from the local community. We would put out all of the submissions that we received and would also ask filmmakers from past years to submit again. The quality was stagnant for a long time, but over the last few years we really started to develop that global reputation and submissions have become a lot more elegant.

This past year we had about 70 films submitted from all over the World from about 16 different countries.

We have a selection committee of about seven to eight people every year. It’s a mixed bag of people from the community but mostly people who have backgrounds in film an art. We try to have a good sampling of people from both a technical perspective, but also from a narrative perspective.

This committee will watch all of the submitted films. It’s a significant time investment and we have open conversations about what we liked or didn’t like over the course of multiple days until we try to gather about ninety minutes of film to showcase, wether that’s spread out over ten films or seven or fifteen films; we just try to stick to ninety minutes because otherwise we start to lose the crowd.

From that point, we have an independent judging panel that the films go to and from then on it becomes completely outside of our hands as the Mosquers are concerned. We want to make sure that it’s a completely fair and objective third party.

We have a conversation with our judges to talk to them about the vision of the Mosquers so that they know what we’re looking for in the different awards, but at the end of the day it’s entirely their decision. We try to get at least one Muslim person on the panel just to make sure that the objective of the Mosquers is being looked after, but certainly two out of the three will have industry experience as filmmakers, directors or producers.

What do you think is the appeal of film and how do you feel that Mosquers has been evolving with that over time?

I think for me the platform presents an opportunity to both showcase and celebrate the Muslim experience while being inviting. It’s a way in which we can bring people of all faiths and backgrounds and even within the Muslim community people of different sects and levels of religiosity. All sorts of different people can come together and just celebrate the diversity of who we are and maybe even learn about what makes us different in a good way and what brings us together.

With film, you can create a much more mainstream appeal and an ability to attract people who probably otherwise wouldn't want to be associated with a Muslim event. As sad as that might be to us, that’s just the reality. I think if we can do it in this environment where it’s safe and without judgement, it’s inviting and not preachy, you’re going to get the opportunity to collaborate with people.

Half of the movies we showed in 2006 when we started wouldn’t even technically work in 2018 because the static and the pixelation would be awful. Now that limitation doesn’t exist. You can film a pretty sweet set up with just your phone. I think the barrier to entry is so low that if you’ve got something to say and if you’ve got a somewhat artistic eye and are willing to invest in a decent microphone, you can produce a pretty compelling short film. So I think that produces and opportunity for us to tap into people and say, “OK, if you’ve got something to say and you can show it and put that narrative together in a compelling manner, the technical stuff it just needs to clear base hurdles and we’ll take it from there.”

In terms of our attendance, it has been a pretty steady growth. Over the last three years, we made a pretty significant leap as it relates to what we would consider our impact; how we’re trying to portray ourselves as an event that’s very much open to the general public, but has an intention of showcasing the diversity and the narratives from around the World of people who identify as Muslims, or non-Muslim film makers and their experience with Muslim people.

It has taken on a life where we’re accomplishing that goal to a pretty significant broad level. This year we had close to 1100 people in attendance.

What was the process or the deciding factor of wanting to make sure that there was an Indigenous presence at the event?

For us it was something that we wanted to do regardless. We wanted to make sure that we had an acknowledgment of Treaty 6 territory and wanted to make sure that local Indigenous communities are respected and acknowledged at the event. However this year, beyond just the acknowledgement, we also had an opportunity to commemorate and honour the life of a leader of our community. Her name is Sana Ghani; she passed away earlier this year in a fatal car accident. She was an amateur filmmaker and an educator in Northern Alberta at Cadotte Lake which is an aboriginal school on a reservation. We had an opportunity to honour her but also wanted to make sure that the children she taught had a chance to be a part of this event because she often used Muslim artists as a way to exemplify to her students the medium of art as a way to share their narrative.

Two of Sana’s former students performed a traditional Cree dance to begin the program and it was phenomenal.

What do you think it was about Edmonton that was a grounds for something like this to flourish?

If you just look at the creativity that’s happening in Edmonton beyond the Mosquers, there’s a lot of work that’s happening here where people are pioneering different things all the time.

As it relates to Mosquers specifically, I think it was more so the fact there was a team of very dedicated individuals who saw what this could become and who were willing to put their minds and hearts into this and see what happens. When you’ve got that sort of strong buy-in from the community, it’s easier to do stuff and begin in a smaller market. In a city like New York or Toronto where there’s so much going on, it’s harder to buy in.

It launching in Edmonton was maybe the ideal scenario because it had the devotion, it allowed it to continue to flourish because of that.

What is your vision for the Mosquers and where do you see it going from here?

There are a few things I would like to see the Mosquers do. One is having more regular programming throughout the year. I do want us to be a recourse for what we’re trying to accomplish which is bridge building, but to do it through art and culture.

If we can do regular workshops for people who are looking for resources to make films or whatever the case may be, I think that would be a really strong way to add value to the Muslim community and broader community at large.

From a programming perspective, I would love to see this continue to evolve maybe into someday being a multi-day festival where you’ve got all sorts of art and culture on display. If we can be the “Muslim Sundance” where people come from all over the world to celebrate art, creativity and film then that would be phenomenal.

As it relates to the actual festival itself, I want to continue to grow in terms of numbers, but more importantly for me is having a crowd that continues to become more diverse. I don’t want to lose who we have, but I wan new faces, different backgrounds and perspectives. That’s what I would consider a bigger success than just having a hundred more people who think and look the same way I do.

To learn more about Mosquers, click here.

This article was produced exclusively for Muslim Link and should not be copied without prior permission from the site. For permission, please write to info@muslimlink.ca.